This topic will be covered in six parts. This is part 4. Check out

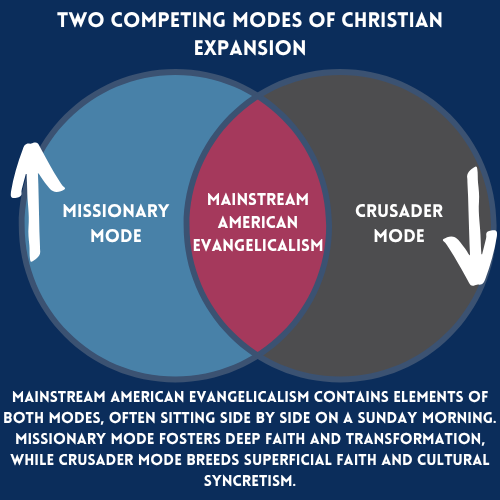

Two Modes of Christian Expansion

It’s at this point that we need to take a step back and assess, and perhaps ask ourselves the question: Does Christian nationalism serve to honor Christ and expand the Christian faith as it claims?

In order to consider that, we need to go back historically and examine how the Christian faith has expanded across cultures and time.

One of the leading experts in understanding the transmission of Christianity was the church historian Andrew Walls. In his posthumous work on the missionary movement, he explains that there are two basic modes through which Christianity has expanded that look and sound similar but have one key difference. Walls writes,

“The crusading mode and the missionary mode are sharply different methods of extending the Christian faith. They grew up in the same areas in the same period; they coexisted and went on side by side. But they are totally different in concept and in spirit. The crusader may invite, but in the end, he is prepared to compel. The missionary cannot compel; the missionary can only demonstrate, explain, entreat–and leave the rest to God. But if the missionary is to demonstrate, invite, and explain, then the missionary has to gain a hearing. That will probably involve learning a language. The conquistadors in the Americas did not trouble themselves much with languages. The Spanish conquest of the Americas is the last of the crusades. Mexico and Peru are conquered, and conquered remarkably quickly. The gods of their empires were destroyed; Aztec and Inca were themselves great empire builders, and the great national shrines of each contained the images of all the deities of all the peoples they had conquered. The shrines reflected a picture of the heavenly world that reflected the earthly. The Spaniards followed a more radical path: they destroyed all the images and built churches over the shrines. Whole populations were baptized, Mexico became New Spain, with the laws and customs of Old Spain, without idolatry, blasphemy, or heresy. Thus by force and violence, and to the accompaniment of brutality, greed, and extortion on the part of the crusader, the new lands of America were brought into Christendom to become subject to the law of Christ and the pattern of Christan nations.”1

He then notes,

“If the missionary cannot compel, then entrance is possible only with the consent of those to whom the missionary goes. It is necessary to find a place, a niche, within the society. The fundamental difference between the crusader and the missionary is the missionary lives and works on someone else’s terms. Though the colonial period brought all sorts of modifications, the generalization remains broadly true even today. The fundamental missionary experience is to live on terms set by somebody else.”2

Which mode does Christian nationalism employ? This is the conundrum.

Christian nationalism often arises from a deep desire to preserve what is good, true, and beautiful in a culture shaped by Christian values. But rather than relying on persuasion, service, sacrifice, and suffering—the way of Christ—it is tempted to secure these ends by leveraging political power. In doing so, it can drift into a crusader mode, seeking to enforce what it can no longer inspire.

Politics: The Only Place of Agency Remaining?

Why are so many Christians so passionately engaged in politics? While politics is indeed a worthy and noble pursuit, some theorize that Christians have been gradually pushed to the margins of other spheres of public life, such as education, media, and the arts. As a result, politics has become one of the few remaining arenas where they feel they can exercise meaningful agency. It’s important to recognize, however, as sociologist James Davison Hunter points out, that politics is also the one institution in society with the legitimate authority to wield coercive power—even violence.

“Within the Christian movement today, it is mainly through political means. That’s the strategy of choice. Get our person in the White House. That’s been the case within for Christians for many decades now. We need, they would say we need to wield the levers of power in order to protect life. Well, let’s understand what the government is, what the state is. The state is the only institution that possesses the legitimate use of coercion, of power of violence. You break the law and the state is the only institution that has the legitimate use of violence against you for having broken the law. So they will talk about defending life, but using the power of coercion, the power of violence. State legitimated violence to achieve that.”3

I contend that, despite their claims to the contrary, many Christian nationalists are driven less by theological conviction and more by a desire to regain a sense of power and agency in a culture where they feel increasingly excluded. When connection, persuasion, and love in the way of Christ seem ineffective or out of reach, they turn instead to the power of the state to accomplish what they feel powerless to achieve through personal or communal witness.

To better understand the dangers embedded in this posture, especially in the nationalism component of Christian nationalism, Paul Miller shows that,

“Nationalism is an ideology of emotion more than ideas, originally created to prop up and justify authoritarian or revolutionary government but founded on vacuous ideas. The danger of nationalism is not that it encourages us to cultivate loyalty to and affection for our country—which is inescapable—but that it endows the state with almost limitless jurisdiction to reshape culture, imagines the nation as a quasi-religious body, and exacerbates sectarian and ethnic cleavages at home. Christians who uncritically buy into nationalism are giving support to an incoherent secular idea with a troubled historical record and making themselves credulous supporters of a dangerous and thoughtless ideology.”4

Not only do Christian nationalists fail to understand theology (part 2), history (part 3), and human nature (part 5), which ultimately results in the perversion of the Christian mission itself, as Russell Moore argues,

“What happens when the motivations of supposedly born-again people seem to be lined up exactly with their tribal boundaries or their base appetites, in a way that would be the same even if Jesus were still dead? Christian nationalisms and civil religions are a kind of Great Commission in reverse, in which the nations seek to make disciples of themselves, using the authority of Jesus to baptize their national identity in the name of the blood and of the soil and of the political order. The gospel is not a means to any end, except for the end of union with the crucified and resurrect Christ who transcends, and stands in judgment over, every group, every identity, every nationality, every culture. Christian nationalism might well ‘work’ in the short term in cementing bonds of cultural solidarity according the flesh. But apart from the shedding of blood there can be no forgiveness of sins. Apart from the Holy Spirit, there can be no newness of life. Christian nationalism cannot turn back secularism, because it is just another form of it. In fact, it is an even more virulent formed of secularism because it pronounces as ‘Christian’ what cannot stand before the Judgment Seat of Christ. Christian nationalism cannot saved the world; it cannot even save you.”5

Identity Protection

Christian nationalism is not about advancing the cause of Christ; it is about identity protection, a psychological coping mechanism that uses faith to justify itself. It’s about preserving a sense of cultural status, all the while sacrificing the gospel or accommodating it to secure it, as Moore points out,

“And yet, in a world in which everything is politics, everything is a culture war, everything is identity protection, religion becomes a useful tool to take all that and make it seem transcendent. When a religion is seen as a political agenda in search of a gospel useful enough to accommodate it, one will end up pleasing those who see the primacy of the politics while losing those who believe the gospel. In many ways, the politicized evangelicalism we see everywhere around us to actual Christianity what the Nation of Islam is to the actual Muslim faith. Both are nationalistic vehicles of identity politics, needing a transcendent creed on which to ride. Culture-warring is easier than conversion because, as George Orwell once wrote of ‘transferred nationalism,’ it ‘is a way of attaining salvation without altering one’s conduct.’ The stakes are much higher, though, if the Christian religion is actually true. As Lesslie Newbigin warned: ‘The confusion of a particular and fallible set of politics and oral judgments with the cause of Jesus Christ is more dangerous than the open rejection of the claim of Christ in Islam, just as the shrine of Jeroboam at Bethel was more dangerous to the faith of Israel than was the open paganism of her neighbors, for the worship of Baal was being carried on under the name of Yahweh.’”6

Moore, citing James Davison Hunter, echoes this idea of Christian nationalism being more of an emotional and psychological reaction to not only being excluded from a place of cultural esteem (which it believes it deserves), but also to the fear of being humiliated,

“James Davison Hunter warned over a decade ago that much of American evangelical ‘culture war’ engagement was based in a heightened sense of resentment, which he defined as a combination of anger, envy, hate, rage, and revenge, in which a sense of injury and anxiety become key to the group’s identity. Often, this sort of rage mixed with anxiety is bound up not so much with a fear of specific policy outcomes but as a fear more primal, more akin to middle school: the fear of humiliation.”7

Moore continues to expand on this “resentment posture,”

“In Hunter’s view, a resentment posture is heightened when the group holds a sense of entitlement—to greater respect, to greater power, to a place of majority status. This posture, he warned, is a political psychology that expresses itself with ‘the condemnation and denigration of enemies in the effort to subjugate and dominate those who are culpable.’”8

Moore goes on to cite Amanda Ripley and her study on conflict. Ripley found that humiliation occurs when two factors happen in rapid succession. The first factor is when our brains have sought to evaluate specific events and then fit those events into our understanding of the world. But the humiliation occurs not by evaluating it, but when we realize that we are at the wrong end of it,

“She argues, ‘To be brought low, we have to first see ourselves as belonging up high.’ She gives the trivial example of her once-ever golfing outing, in which she missed the ball over and over again. She laughed at herself, she said, but she didn’t feel humiliated. That’s because, she writes, being good at golf is not part of her identity. If Tiger Woods—renowned to be the best golfer in the world—performed the same way, it would feel humiliating, especially on camera before an entire watching world.”9

In this light, Christian nationalism emerges as a reaction to deep feelings of isolation and humiliation. When these emotions take root, they often trigger what neurotheologian Jim Wilder describes as “enemy mode.”

Next week, we’ll take a closer look at what happens when the gospel itself is viewed—and lived out—in enemy mode.

Andrew Walls, The Missionary Movement from the West: A Biography from Birth to Old Age (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2023), 14.

Walls, 17.

James Davison Hunter, “#247 | Building Unity Amid Polarization: Calling You Deeper Than Media Headlines with James Davison Hunter, Pt. 2”, Those Who Serve the Lord podcast, March 18, 2025.

Paul D. Miller, The Religion of American Greatness, 109.

Russell Moore, Losing Our Religion, 120.

Ibid., 120-121.

Ibid., 121-122.

Ibid., 122.

Ibid., 123.