Patrick Mahomes, quarterback of the Kansas City Chiefs, has already cemented his place as one of the greatest quarterbacks in NFL history. Given his prominence, it’s no surprise that the Christian community has been quick to claim him as one of their own—a high-profile ambassador of the faith. His public statements about his faith, such as his 2020 post-Super Bowl testimony, have been widely celebrated:

“Before every game, I walk the field and I do a prayer at the goalpost. I just thank God for those opportunities and I thank God for letting me be on a stage where I can glorify Him,” Mahomes said in the FCA video. “The biggest thing that I pray for is that whatever happens, win or lose, success or failure, that I’m glorifying Him.”1

Mahomes’ words are commendable. Any public acknowledgment of God is refreshing in a world increasingly hostile to faith. Yet what strikes me is how quickly the Christian community has rallied behind him as a model of faith when he said this—glossing over the fact that he was living with his girlfriend and having a child with her before he ever proposed marriage.

This isn’t meant to demean Mahomes; he is not a pastor, nor is he a theologian. And yes, I know that he is married now. Praise God for that. Before you leave angry comments or send me angry texts, I know that we are all sinners, and his life happens to unfold under the microscope of fame.

Desperately Seeking Credible Christian Witness

What concerns me is how easily the modern church seems willing to move the goalposts of Christian witness—so desperate to find a cultural win that we are willing to embrace anyone who gives a passing nod to faith: Mahomes, Kanye West, Justin Bieber, Beyonce, Selena Gomez, Chris Pratt, just to name a few.

Because we are willing to embrace any kind of Christian witness, there are no longer any criteria for what is acceptable and what is not. For example, Mahomes’ wife, Brittany, posts Bible verses alongside pictures of her in a bikini or other thirst traps. What kind of message does that send?

Could it be that Mahomes is true to his faith? Could it be that the faith Mahomes represents is not biblical Christianity but an entirely different faith entirely?

In his 2009 book, Souls in Transition, which was based on the largest study of religion in American youth, sociologist Christian Smith concluded,

“Most emerging adults have religious beliefs. They believe in God. They probably believe in an afterlife. They may even believe in Jesus. But those religious ideas are for the most part abstract agreements that have been mentally checked off and filed away. They are not what emerging adults organize their lives around. They do not particularly drive the majority’s priorities, commitments, values, or goals. These have much more to do with jobs, friends, fun, and financial security. Yes, basic religious beliefs indirectly help people to be good. But that comes out of deeply socialized instincts and feelings, not anything you have to really consciously think about or actively commit to. In this way, most emerging adults maintain various religious beliefs that actually do not seem to matter much.

…More generally, it was clear in many interviews that emerging adults felt entirely comfortable describing various religious beliefs that they affirmed but that appeared to have no connection whatsoever to the living of their lives.”2

That sounds like so many evangelical celebrities today. They affirm the basics of Christian faith, but their lives lack its substance.

The Real Religion of America

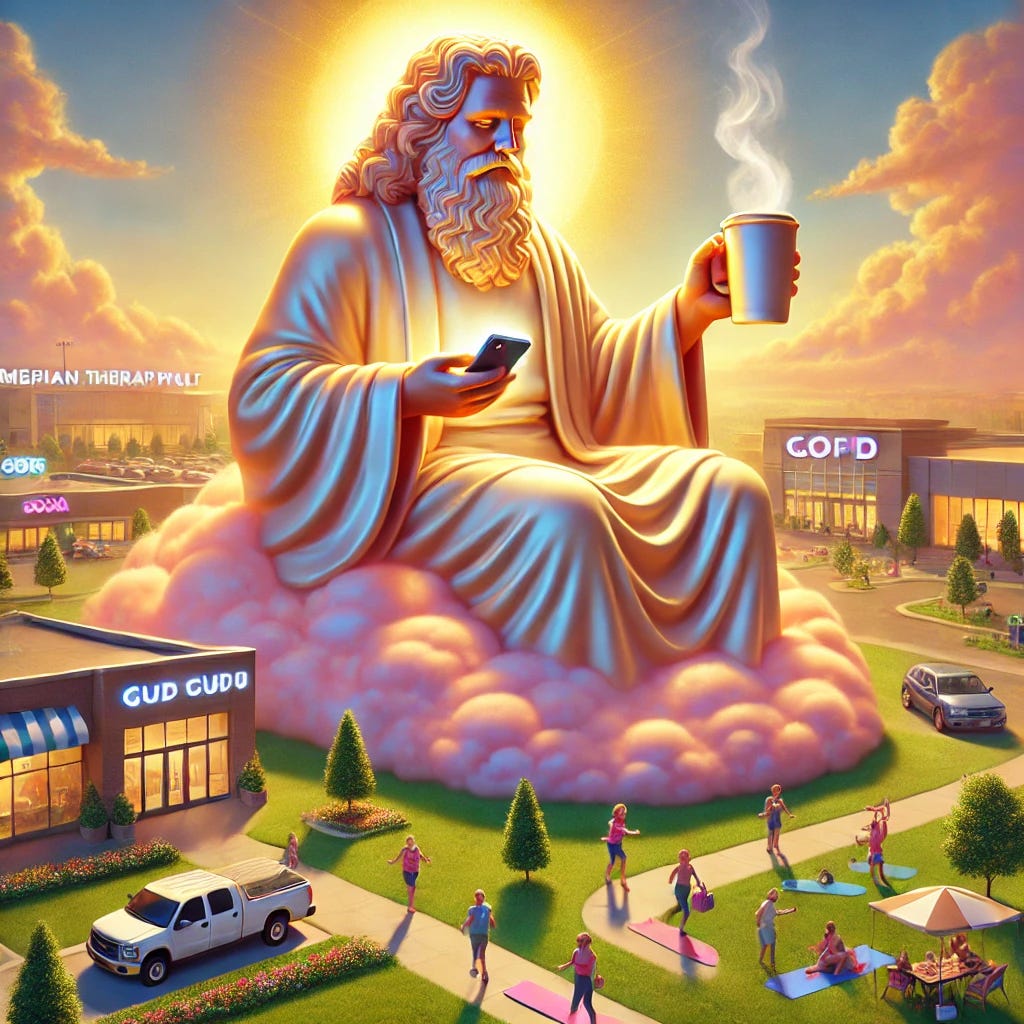

Smith goes on to argue that the real religion of America is not Christianity but Moral Therapeutic Deism (MTD) under the guise of Christianity. In his previous book, Soul Searching, he concluded that followers of MTD had five core tenets,

-

A God exists who created and watches over the world.

-

God wants people to be good, nice, and fair to each other.

-

The central goal of life is to be happy and feel good about oneself.

-

God is not particularly involved in one’s life except when one needs to solve problems.

-

Good people go to heaven when they die.3

On the surface, this sounds benign—perhaps even vaguely Christian. But at its core, MTD is not the gospel. It is a counterfeit faith, reducing Christianity to little more than self-help with a divine mascot.

Bonhoeffer’s Assessment

If we’re honest, this is what many of our churches have been implicitly teaching. Over the years, I’ve been in hundreds of churches across the country of all sizes—traditional, contemporary, seeker-friendly, and even those considered theologically conservative. Most would reject MTD on paper. They would insist they preach Jesus Christ and him crucified. Explicitly, they communicate that the gospel is about getting you into heaven and God offering a better life, but implicitly, they communicate that nothing else really matters—holiness, the cost of discipleship, etc., (except politics!) and they have a skewed understanding of how the kingdom of God transforms the totality of life here and now.

At its core, MTD is a radical gospel reduction—keeping the forgiveness of sin but sheering it of sanctification. It is the cheap grace that the German Pastor-theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote of,

“Cheap grace means the justification of sin without the justification of the sinner. Grace alone does everything, they say, and so everything can remain at it was before.”4

His point is that we give credence to the idea that we can’t save ourselves and that God does everything, but such an idea is a perverted understanding of grace. Bonhoeffer continues,

“Instead of following Christ, let the Christian enjoy the consolations of his grace! That is what we mean by cheap grace, the grace which amounts to the justification of sin without the justification of the repentant sinner who departs from sin and from whom sin departs. Cheap grace is not the kind of forgiveness of sin which frees us from the toils of sin and from whom sin departs. Cheap grace is not the kind of forgiveness of sin which frees us from the toils of sin. Cheap grace is the grace we bestow on ourselves.

Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession, absolution without personal confession. Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.

Costly grace is the treasure in the field; for the sake of it a man will gladly go and swell all that he has. It is the pearl of great price to buy which the merchant will sell all his goods. It is the kindly rule of Christ, for whose sake a man will pluck out the eye which causes him to stumble; it is the call of Jesus Christ as which the disciple leaves his nets and follows him.

Costly grace is the gospel which must be sought again and again, the gift which must be asked for, the door at which a man must knock.

Such grace is costly because it calls us to follow, and it is grace because it calls us to follow Jesus Christ. It is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life. It is costly because it condemns sin, and grace because it justifies the sinner. Above all, it is costly because God did not reckon his Son too dear a price to pay for our life, but delivered him up for us. Costly grace is the Incarnation of God.”5

That’s MTD in a nutshell—it is the cheap grace of a reduced gospel, a Christless Christianity.

It’s no wonder then that Christianity has lost the interest of people. We have neutered the gospel, turning it into a privatized version of self-help. As one young woman once summed it up to me:

“My Christian faith is very important to me. It’s privately wonderful but publicly useless.”

That’s the tragedy. The gospel we’ve been preaching is great at securing a ticket to heaven, providing some moral guidance, and offering some comfort in times of crisis—but it doesn’t seem to have much to say about any other part of our lives.

MTD is a form of Christianity that has nothing to say about our everyday lives: business, politics, science, art, or the way we scroll through our phones. It has little to offer when it comes to racial reconciliation, immigration, foreign policy, or how we raise our kids. No wonder so many Christians have dechurched. They got their sins forgiven—what else is the church for?

What’s Really Going On Here?

Evangelicals have been playing the celebrity game for decades now—desperately trying to find someone famous who will validate the faith in the public square. But the whole impulse is upside down.

We’re not supposed to ride the coattails of cultural relevance to spread the gospel. The early church turned the Roman Empire upside down not because they had celebrities on their side but because they lived such radically different lives that the world couldn’t ignore them.

Instead, we’ve traded in the prophetic power of a holy people for the cheap PR of a famous person saying, “I thank God.”

Why Do We Do This?

Honestly?

Because we’re deeply insecure.

We want so badly for Christianity to be seen as credible that we’ll hitch our wagons to anyone who mentions God on a microphone—whether or not their lives bear the fruit of the kingdom.

It’s the same drive that makes us plaster “In God We Trust” on our money and fight for prayer in public schools—as if cultural symbols will somehow give Christianity back its power.

It’s the same impulse tempting us with promises of influence and affluence. All it costs is our cumulative Christian witness—a price far too many are willing to pay.

But that’s not how the kingdom works.

The power of the gospel is never in having the right celebrities, the right laws, or the right political influence.

The power of the gospel is in the crucified people of God living as a countercultural community—a new humanity that shows the world what life under the reign of Jesus looks like.

Some Verses for Consideration

Before you leave an angry comment or accuse me of legalism, consider this verse from Hebrews 2:14,

“Strive for peace with everyone, and for the holiness without which no one will see the Lord.”

This verse may be one of the uncomfortable verses in the New Testament today—especially in the American evangelical landscape.

But it’s this verse that absolutely shreds Moral Therapeutic Deism and the whole “I prayed a prayer, God loves me, I’m good” approach to Christianity.

The verse contains two commands—both are active, both are communal, and both are non-negotiable:

The first is that we are to strive for peace with everyone. The Greek word is dioko—literally pursue, chase after, hunt down. This isn’t some passive, wishful thinking like, “Hey, if this happens, it happens.” Nope. It’s relentless action.

But what kind of peace is this? Typically, we think of peace as simply the absence of conflict, but it’s much more than that; it’s shalom. It’s about wholeness in relationships—both inside and outside the church.

Secondly, we are to strive for holiness, without which no one will see the Lord. It’s not optional to God. Now, here’s the knife to the heart. If peace is horizontal, holiness is vertical.

Notice what the text doesn’t say: “Holiness is a nice add-on for the really committed.” It doesn’t say, “Holiness is for the super-spiritual.” It says that without holiness, no one will see the Lord.

What are we talking about? What do we mean when we use the word holiness? The word here is hagiasmos, and it means the process of being set apart. This isn’t some mystical, monk-like detachment from the world where we live as floating avatars over the everyday cares of our lives. Not at all. It’s something else entirely.

It’s God-shaped lives in the middle of the world—what Lesslie Newbigin called “holy worldliness”—living in the world with a different set of desires, rhythms, and loves. It’s not withdrawal from the world or blending in, but showing the world a different way to live—the way of God’s kingdom.

But that vision of God’s kingdom is offensive to evangelicals today because it requires a loss of cultural capital and status. We don’t want a different way to live—we want the gospel to affirm the lives we’re already living. We’ve trimmed holiness out of the gospel and replaced it with self-affirmation and good vibes Jesus—a Jesus who makes us feel better, not different.

MTD guts the gospel of holiness. When you cut holiness out of the gospel, you’re not just trimming the edges—you’re cutting out God himself: his holiness, justice, and wrath—and the substitutionary death of Jesus. The cross means nothing in MTD. What you’re left with isn’t the thrice-holy God of the Bible—it’s a god made in our image who requires nothing and gives nothing, a cosmic life coach who exists to bless our dreams, not confront our desires.

The hard truth is that we don’t want this God. We want a god who wants what we want.

We want influence without holiness.

We want platforms without sanctification.

We want resurrection without crucifixion.

We want the kingdom without the King.

At this point, you may be wondering what I am getting at. Well, let me tell you.

I think that the gospel is much bigger than we have understood it and that we have made it so small and removed from public life that it has become nothing better than self-help.

Jesus didn’t just come to get us into heaven and escape from this world. He came to get heaven into us so that we might engage the world and participate in his mission for the world—to reconcile all things to himself (Colossians 1:20). He didn’t come to give us an escape plan from the world, but a plan of kingdom invasion, as C.S. Lewis wrote,

“Enemy-occupied territory—that is what this world is. Christianity is the story of how the rightful king has landed, you might say landed in disguise, and is calling us all to take part in a great campaign of sabotage.”6

The “sabotage” is nothing less than the rightful King reclaiming his creation and inviting us to participate in that reconciliation mission for all things. This causes us to rethink what it means to be a follower of Christ today.

What does this mission mean in our vocation?

What about business? Economics? Politics?

What about issues like immigration?

What about the education we give our children?

This mission permeates everything.

Part of our issue is that by having a reduced gospel, we have removed ourselves from having Jesus speak to the full breath of human experience, but that can’t continue; he won’t let it, as Abraham Kuyper noted,

“There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, ‘Mine!'”

If Christ is to be sovereign over all things, we must live in a way that reflects that truth. This mission is not carried out by crusaders conquering through power, coercion, or domination, but by embracing love, sacrifice, and humility.

Moral Therapeutic Deism is subtle because it co-opts Christian language for its use. It caters to our desires and, while offering therapeutic comfort, can turn violent when that comfort is threatened and must be defended at all costs.

How MTD retranslates the Biblical Gospel:

Biblical Gospel Moral Therapeutic Deism

*Follow Jesus *Be a Good Person

*Die to yourself *Believe in yourself

*Seek first the Kingdom of God *Chase your dreams

*Lose your life to find it *Find yourself

*Suffer with joy *God wants you to be comfortable.

*Join God’s mission *God has a wonderful plan for your life (as long as

it leads to the American Dream).

The Antidote to MTD

The antidote to Moral Therapeutic Deism isn’t just sharper apologetics or deeper theological systems—it’s the new humanity of God’s kingdom embodied in everyday life. That’s where missioholism comes in.

Missioholism sees the good news not as an isolated message but as the heartbeat of everything—the announcement that Jesus is Lord over all. But Christ’s lordship only makes sense within the larger framework of the kingdom of God—a redemptive mission creating a new kind of humanity, embodied in a distinctive, transcultural community called the church.

When I was a kid, I loved camping out in tents. The problem was that I wasn’t big on reading directions. I would take a quick glance at the instructions, notice that I had all the poles, stakes, and fabric, and start piecing it together. I usually ended up with a lopsided tent—extra pieces left over, nylon sagging, and barely enough room for one person. It wasn’t until I went back, carefully followed the instructions, and rebuilt the framework that everything fit together—and there was room for more people inside.

That’s what’s happening with much of theology today. It assumes the framework without examining it, focusing on one vital truth—Christ died for our sins—while missing the bigger picture of what God is doing. The gospel is more than personal salvation; it’s the announcement of God’s kingdom breaking into the world, forming a new humanity who are not just saved from something but saved for something—to embody his kingdom together, in every sphere of life.

For many of us, such language seems confusing—we do not see Christ engaged in modern life. We have hard lines separating the sacred and the secular—and even that conveys the next idea that has reshaped the gospel that we will unpack next week—the Enlightenment and the sacred/secular split.

The real question before us is this: What is the gospel really about? It’s more than just making you a good person, happy, or giving you an escape from the world. Jesus didn’t come to get us out of the world. He came to get heaven into us so that we can live out his mission of reconciliation and transformation in the world.

Putting It All Together

We stand at a crossroads in Western Christianity. Will we continue to cling to a reduced gospel—one that conveniently fits into the American Dream? Or will we embrace the gospel as a revolutionary summons to live as Christ’s body in a broken world?

But before you answer, count the cost.

Changing allegiances will cost you family, friends, and comfort. You may lose respect. Your reputation will suffer. It will bring shame, accusations, and exclusion. You may feel fear. You may experience financial loss. You may find yourself outside the tribe you’ve always belonged to.

And here’s the painful truth—I’m not talking about rejection from the world. I’m talking about rejection from those sitting next to you in the pews—those who have baptized Moral Therapeutic Deism as biblical Christianity.

There is a cost, but it’s worth the price.

A gospel without holiness, without self-denial, without mission is no gospel at all. It’s a counterfeit—offering comfort without the cross, community without commitment, and heaven without surrender.

It’s time to reclaim the full gospel—a gospel that changes everything.

It starts with us.

Will we be disciples of Jesus—marked by holiness, humility, and mission? Or will we settle for a gospel of good vibes and self-affirmation?

The choice is ours.

Jon Ackermann, “Chiefs claim Super Bowl LIV: Owner Clark Hunt thanks the Lord, MVP Patrick Mahomes aims to glorify Him,” February 3, 2020, https://sportsspectrum.com/sport/football/2020/02/03/chiefs-super-bowl-owner-clark-hunt-thanks-lord-mvp-patrick-mahomes-glorify-him/, accessed on 3 March 2025.

Christian Smith, Souls in Transition, 154.

Ibid.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship, trans. R.H. Fuller, rev. ed. (New York: Touchstone, 1995), 43.

Ibid, 44-45.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, p. 46.