“It’s just business,” my friend said.

He was in his mid-20s, strong, ambitious, and driven. Born in Russia, he had immigrated to America as a child and grew up in the mid-Atlantic. Every Sunday, he faithfully ran the sound system at his local Slavic Baptist church, a congregation of 150 founded by immigrants who had fled communism after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Many in the church were entrepreneurs, eager to seize the opportunities that had been denied to them for decades. They possessed a strong work ethic and a determined attitude, and success followed. The congregation was known for its conservatism and unwavering adherence to Scripture.

Slavic Baptists are a unique group—staunchly conservative, biblically fundamentalist, yet distinct from their tribal brethren back in their homeland. Their faith resembled that of the Baptists in America of the 1980s, untouched by the shifting theological trends of the West. They were stuck in time, obstinately adhering to the expression they had when they came to the U.S., while their homeland brethren had changed over time.

Their success was evident even in the church parking lot, which looked more like a luxury car dealership than that of a working-class church members—BMWs, Mercedes, Escalades, Audis, and Lexus SUVs lined the rows. It all started with a few families who discovered that landscaping was a lucrative business. Their success inspired a wave of imitators, and before long, the church was filled with landscapers.

One day, when I was guest speaker at one of their conferences, I overheard my friend boasting to another church member about how his company had deliberately undercut a competitor—another family from the church—pushing them to the brink of financial ruin. I don’t recall all the details, but I remember feeling uneasy. What he had done seemed not just unethical but possibly illegal. He noticed my silence and asked what was wrong.

I hesitated, then asked, “Is this really how we should treat a brother in Christ?”

He shrugged. “It’s just business. It’s not church. It’s just business.”

I walked away unsettled. Was he right? If business and faith were separate, why did this bother me so much?

Years later, I still think about that moment. For him, it was just another conversation, quickly forgotten. But for me, it was a turning point. What kind of belief system could justify treating people this way?

Over the years, I have concluded that I can only accurately describe through an illustration.

God-Land and Beyond God-Land

This young man lived in a city that I have come to call “Beyond God-Land,” a place that had once been part of “God-Land” but was divided generations ago. Some clever men had built a wall, separating the two. Now, there were two realms: one where the King’s authority was widely acknowledged and another where it was ignored.

The King had once ruled it all, but he had left with a promise to return. In his absence, Beyond God-Land established its own laws—laws shaped by power, reason, and radical autonomy. Meanwhile, the people of God-Land lived in freedom and joy, though many crossed into Beyond God-Land each day for work. At the checkpoint, they were searched for anything that might connect them to their homeland.

The self-appointed city council of Beyond God-Land declared that God-Land was illegitimate, its laws had no authority in public life, and its King was irrelevant. Yet, despite their proclamations, both lands—whether they admitted it or not—were still under the rule of the King beyond the sea.

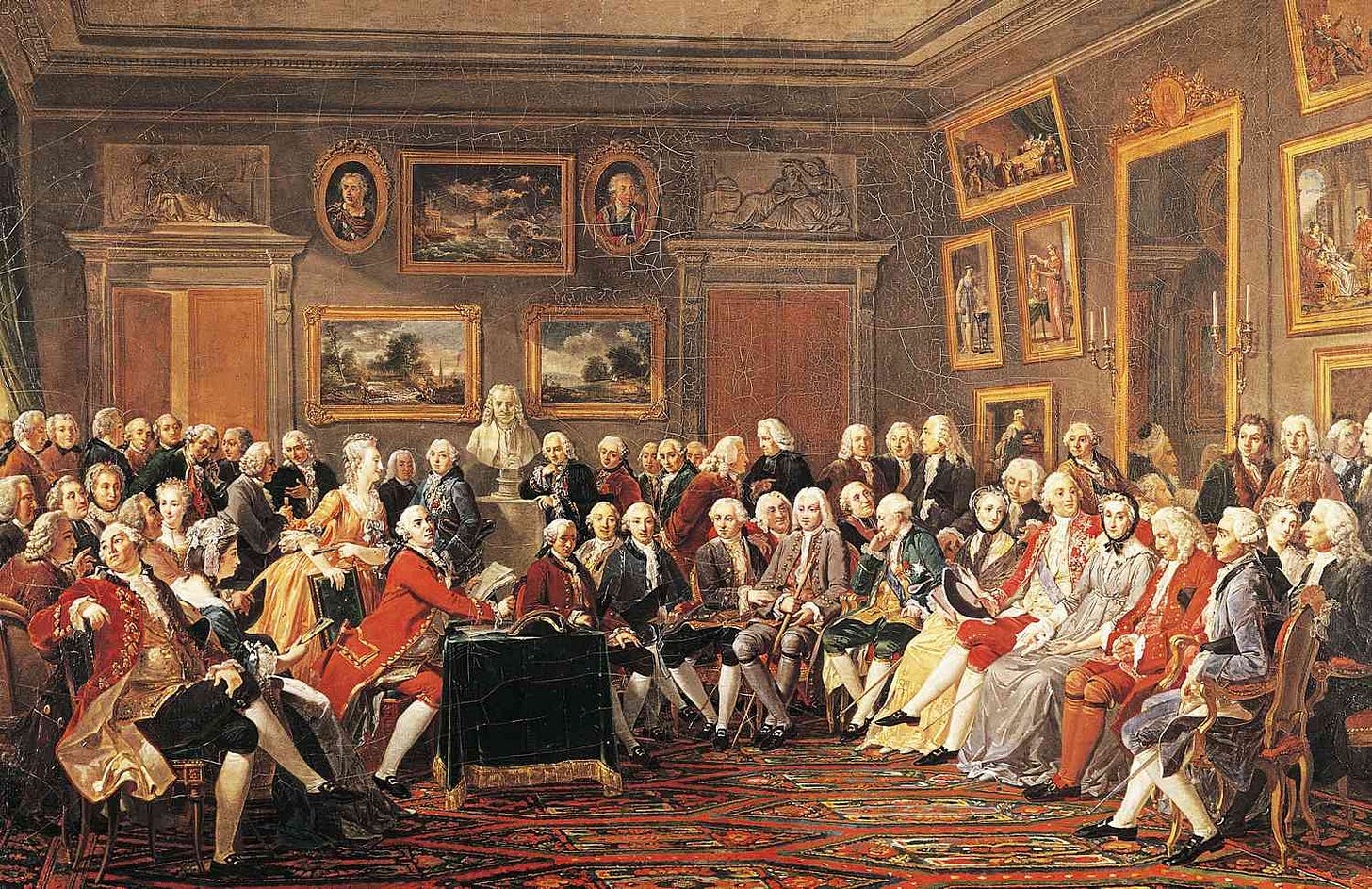

Of course, if you’re following my little story, I am trying to illustrate how the modern world was created. It was the Enlightenment thinkers who actually shaped our understanding of the world because it was they who created the artificial partition that so affected my friend.

Names such as Hume, Locke, Spinoza, Descartes, Rosseau, Voltaire, and others had created the partition because they wished to deny God’s existence or his authority over the world, so they created a world that he is not allowed to influence, and for my friend, it was his business—that operated according to a different set of rules beyond God’s purview.

A. The Great Replacement

When you take God out of the equation, you have to replace him with something—and that is what the Enlightenment was all about—recreating an entirely different intellectual world. James Davison Hunter described it,

“…the Enlightenment was a revolution generated by an alternative network of leaders, providing an alternative cultural vision (a new anthropology, epistemology, ethics, sociality, and politics), established in part through alternative institutions, all operating at the elite centers of cultural formation.”1

In essence, the Enlightenment was revolutionary in that it sought to reframe all of life—our purpose as humans, how we lived in the world, how we can know what we know, and how we engage the world.

How did it practically do that?

B. Five Ways the Enlightenment Distorted the Gospel.

1. The Secular/Sacred Split.

In our story, a partition was created. On one side is God-Land, where the Sacred is permitted to dwell. On the other side is Beyond-God Land, where the Sacred is barred from entry. This mirrors our modern world, where HR departments, school boards, and governments operate under the assumption that God must not influence public life.

In God-Land, you are free to worship as you choose—but you must leave that behind when you step into Beyond-God Land. The problem is that this partition is artificial and unstable. No society is truly secular. Every culture, without exception, is shaped by some form of religiosity—some ultimate authority that defines what is right and wrong, what is valuable, and what must be obeyed.

In Beyond-God Land, the city council has set itself up as that authority, claiming human reason as its foundation. But reason does not exist in a vacuum. It is always shaped by a moral framework—one formed by faith, family, education, or society. These frameworks define what is good and desirable, as well as what is bad and unacceptable. The real question is: Who gets to decide what is good and what is bad?

Most of us take our moral framework for granted—until we encounter someone who challenges it. Consider Indonesia, where public whipping is an accepted form of punishment. To Westerners, this seems repugnant. But why? What right do we have to say it is wrong? Where did we get that belief?

Or think about a potential Supreme Court Justice being vetted for appointment. Inevitably, they are asked about their faith. Why? Because the interviewers want assurance that their beliefs won’t influence their judgments. But this is impossible. No one can suspend their moral framework entirely. We might manage it for a moment, but over time, our worldview will shape our decisions.

There is no such thing as a neutral culture or a worldview-free society. The sacred/secular divide is a modern invention—and it collapses under scrutiny. Every culture, even those that claim neutrality, establishes its own moral authority. In doing so, it defines all others by its own standard, making itself the ultimate measure of truth. This is self-contradictory, and Christ will have none of it.

All of life belongs under God’s sovereignty. He cannot be banished to the private realm. That’s what Nietzsche was talking about when he said, “God is dead.” Michael Goheen and Craig Bartholomew, in their Living at the Crossroads, note,

“Over a century ago the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) told a chilling parable of a madman who makes the startling accusation we have killed God: ‘We have killed him—you and I. All of us are his murderers.’ (Nietzsche was alluding to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, which we will examine in the next chapter, when Western culture excluded God from public life.) ‘How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?’ the madman asks. ‘Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?’”2

Nietzsche was right in his assessment, at least in regard to how we allow God to influence public life. And if God is denied influence, then he must be replaced—and the question is, by what?

2. Secularized Eschatology.

The Bible teaches that history is moving toward a definitive goal—the restoration of all things. However, the Enlightenment, after removing God from public life, had to redefine the biblical vision of the kingdom, restoration, and human flourishing. It replaced God’s redemptive plan with a secularized eschatology—one driven by human reason, technological advancement, and the belief in inevitable progress. Instead of placing hope in God’s work, it placed hope in human self-sufficiency.

I first encountered this perspective a little over 30 years ago as a high school senior, just beginning to understand what it meant to follow Christ. One of my closest friends, Chris, did not share my faith. He was widely regarded as the most knowledgeable in our class—especially when it came to geopolitics—and he saw Christianity as nice but unimportant and an impediment to human progress.

One day in English class, our teacher posed the question: “Will we see peace in our lifetime?”

Without hesitation, Chris answered, “Yes!” He cited human progress, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the growing number of peaceful nations as evidence that the world was moving toward harmony.

I wasn’t well-versed in geopolitics, but something about his answer didn’t sit right with me. So I disagreed. A debate quickly erupted, dividing the class into two camps. Voices rose, frustrations mounted, and the discussion grew intense.

Finally, my friend, confident he had the decisive question to dismantle my argument, asked, “Why exactly do you believe we won’t see peace in our lifetime?”

My answer was simple: “Because I can’t even agree with you.”

The room fell silent. I wasn’t trying to be clever—I was stating the obvious. If two high school students from our small town who grew up together couldn’t reach a consensus on something as fundamental as world peace, how could entire nations?

That debate exposed two contrasting worldviews. My friend truly believed human progress would lead to peace. But I saw something he didn’t: human progress is still tainted by sin. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for peace, nor does it mean humanity is doomed. It simply acknowledges the reality of a broken world.

Secularized eschatology promises that human advancement will eventually bring perfection. But cracks in that vision are becoming harder to ignore. Just recently, a repairman working at my house struck up a conversation about AI. As we discussed how technology is replacing jobs at an alarming rate, he paused and said, “It makes me wonder… What are we even here for? What is our purpose?”

His question lingers. The secular vision of progress is unraveling, and beneath it lies a deeper longing—one that technology cannot satisfy.

3. Reason > Revelation

The Enlightenment ushered in a tectonic shift in how knowledge, truth, and authority were understood. While previous generations saw these things being rooted in Scripture, the Enlightenment put human reason in the driver’s seat.

Several of the Enlightenment thinkers sought to free man from the constraints of what they considered to be a religious monopoly of oppression and subjugation in order for human progress to flourish.

One of the most notable examples of this mindset is Thomas Jefferson, one of the greatest Enlightenment thinkers in American history. Jefferson took a razor blade to the Bible—literally. He sought to rewrite the Bible based on his view of the world and meticulously cut out all passages he deemed to be irrational or unscientific—thus removing miracles, claims to Christ’s deity, or anything else that offended Enlightenment sensibilities. As James Davison Hunter wrote,

“As a man of the Enlightenment, Thomas Jefferson himself gave voice to his generation’s shared ideal: ‘Enlighten the people generally,’ he wrote in 1816, ‘and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like evil spirits at the dawn of day.’”3

What remained was an entirely different faith—a moral philosophy draped in Christian language but stripped of its supernatural core. It was no longer the confessional faith of historic Christianity but had instead become the acceptable religion of Enlightenment ideals.

This version of faith was opaque enough that later admirers could project their own beliefs onto his words, seeing in them whatever version of God they preferred. This shift laid the foundation for secularization, the privatization of faith, seeing the Bible as myth, and along with it, the idea that religion was a personal choice rather than public truth.

#4. Redefinition of freedom: Freedom within vs. Freedom from

Embedded within the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason over revelation was a redefined concept of freedom.

In the biblical view, freedom is not merely the absence of restraint but the ability to live rightly within God’s design. True freedom is found through obedience to Him, aligning with his will, and flourishing within the order he has established.

In contrast, the Enlightenment reframed freedom as freedom from—freedom from God’s authority, his design, and the constraints of divine order. In this view, to be truly free is to cast off any external limitations, particularly those imposed by religious belief.

This shift in thinking is evident in many modern debates, including the conversation surrounding transgenderism. Many today seek freedom from their own bodies, believing that their physical form is an obstacle to becoming their “true” selves. Yet, Scripture does not present freedom as an escape from reality but as the ability to live within the reality God has created. In pursuing an unrestrained, self-defined freedom, the transgender movement—like many other modern ideologies—seeks the wrong kind of freedom.

The contrast is stark:

-

Biblical freedom is about living in the right relationship with God, within the order he has established.

-

Enlightenment freedom is about being freed from God altogether.

What does this mean in practical terms? Simply put, when freedom is defined as liberation from God’s design, anything becomes permissible. Freedom is no longer anchored in objective truth or a transcendent foundation; instead, it morphs into whatever one desires it to be. This can manifest in extreme ways—whether it’s a man identifying as a woman, marriage to an object, or even the unrestricted right to take another life.

Yet, this supposed “freedom” brings its burdens. With limitless options and no guiding foundation, individuals are left to construct their identities from an overwhelming array of choices. The pressure to define oneself—amid cultural expectations and shifting social norms—creates not liberation but anxiety. The fear of choosing wrongly, of being rejected, or of failing to live up to one’s self-created identity only deepens the confusion and distress.

In the end, the Enlightenment’s redefinition of freedom has not led to human flourishing but to profound instability and confusion. Only in Christ—the source of true freedom—do we find the rest, security, and identity we were created for.

#5. A False Universal Story.

We are storytelling creatures. We don’t just think in abstract propositions—we tell stories. Stories help us make sense of the world, communicate ideas, and shape our identities. Whether they are lighthearted, tragic, or deeply personal, they serve as a lens through which we understand ourselves and our place in history.

Certain stories have profoundly shaped our collective identity in the United States. We love the underdog narrative, whether it’s the real-life tale of George Washington leading the Continental Army against the mighty British Empire to secure American independence or the fictional saga of Rocky Balboa triumphing over Ivan Drago. These stories inspire us and reinforce the idea that perseverance and grit can overcome even the greatest odds.

But underdog stories aren’t the only ones that define us. We’re also captivated by rags-to-riches tales, where the downtrodden rise to success against all expectations—like the orphan Annie finding a new life or Abraham Lincoln emerging from a log cabin to become president. These stories reflect a deep-seated belief in opportunity, hard work, and the possibility of transformation.

Stories shape not just our entertainment but our culture, values, and worldview. They tell us who we are, who we should aspire to be, and what we should strive for. But the question remains: What stories are shaping us today? And just as importantly, do they lead us toward truth or away from it?

The biblical story is not just one narrative among many—it is the true and universal story of the world. As Goheen and Bartholomew explain:

“Thus, the gospel is public truth, universally valid, true for all people and all of human life. It is not merely for the private sphere of ‘religious’ experience. It is not about some otherworldly salvation postponed to an indefinite future. It is God’s message about how he is at work to restore his world and all of human life. It tells us about the goal of all history and thus claims to be the true story of the world.”4

The Enlightenment, in its exaltation of human reason, pushed aside the biblical narrative of creation, fall, redemption, and restoration—reducing it to a matter of personal belief rather than public truth. In its place, a new grand story took hold—one that crowned human progress, science, and reason as the ultimate forces shaping history. This shift redefined truth, morality, and purpose, replacing God’s design with the pursuit of self-determination.

This is the foundation of today’s gender identity debates, as well as issues like abortion, euthanasia, and sexual ethics. It’s why your friend justifies her abortion, why your sister believes marrying another woman is right, and why your great-uncle views assisted suicide as a dignified choice. It’s why so many couples see no need for marriage, living together without a second thought. In this world, the only law that matters is the one inside you.

But every story has consequences. When a culture embraces a false narrative, it doesn’t just reshape individual lives—it alters entire societies. The Enlightenment’s promise of progress, severed from divine authority, has led to profound moral confusion and the destruction of countless lives.

Without a transcendent reference point, truth fractures into “my truth” rather than “the truth.” Freedom is no longer about living rightly within God’s design but about asserting autonomy—no matter the cost. Human identity, justice, and purpose become fluid, dictated by cultural trends rather than fixed in eternal truth.

The question before us is this: Will we continue living by a story that leads to fragmentation and meaninglessness? Or will we return to the true story—the only one that provides coherence, purpose, and ultimate restoration?

B. A Better Way Forward

The Enlightenment is a Christian heresy. It’s hard to remove ourselves from its deleterious effects of understanding truth, freedom, purpose, and individual autonomy, but missioholism offers us a way forward by challenging these assumptions in several key ways:

#1. Restoring the True Story of the World

While the Enlightenment fragmented reality, missioholism recaptures it by placing the Scriptures as authoritative and casts the biblical story of creation, fall, election, redemption, mission, and restoration—as the true story of the whole world. Missioholism refuses to reduce the gospel to a solitary task, private endeavor, or solely individualistic salvation but keeps the tension of the gospel’s individual, communal, and cosmic nature. It presents the gospel not as private truth, but public truth that speaks to all aspects of life.

#2. Reclaiming Biblical Freedom

The Enlightenment redefined freedom to be freedom from God as expressed in human autonomy. In contrast, missioholism affirms that true freedom is not found in self-determination but in living rightly within God’s design. Freedom is not about rejecting divine order but about being restored to it, finding fulfillment in obedience to God and participation in his mission.

#3. Reuniting Truth and Mission

The Enlightenment exiled religion to the realm of private faith and saw its mission in terms of human progress. Christian mission often accepted this idea and reduced the concept of kingdom and mission to a strictly spiritual sense and otherworldly salvation. Missioholism rejects this dichotomy, affirming that truth is inherently missional and public. The gospel is not an abstract set of doctrines but a call to live in alignment with God’s redemptive purposes in every sphere of life: intellectual, social, and cultural.

#4. Redirecting the Enlightenment’s View of Progress

The Enlightenment placed faith in human progress, believing that reason and technological advancements would lead to societal nirvana. Missioholism challenges this false optimism by simultaneously recognizing both the dignity and the depravity of humanity and recasting it within the biblical narrative whereby the cultural mandate and history are moving to a desired end—the restoration of all things. However, missioholism sees true renewal and restoration coming only through Christ and displayed through the work of his people.

#5. Restoring the Communal and Embodied Nature of Faith

Before the Enlightenment, Christianity was expressed in more of a communal fashion, but the Enlightenment reduced faith to a personal and internalized experience, severing it from its communal nature as being an embodied reality. Missioholism resists this hyper-individualism by emphasizing the role of the church as the new humanity of the new creation. The mission of God is not an abstract idea but is lived out through a redeemed community that reflects the kingdom in real, tangible ways.

#6. Resisting the Enlightenment’s Reduction of Reality

The Enlightenment led to a disenchanted view of the world, whereby the spiritual was dismissed in the face of the material, and the material became the only valid realm of truth. Missioholism corrects this view by recognizing the spiritual nature of the Scriptures and of life and sees them underneath God’s reign.

Conclusion: A Call to a Better Story

The Enlightenment was a Christian heresy—a reshaping of the Christian story that denied its claim to public truth, divine authority, and supernatural reality. In its place, it enthroned reason, progress, and human autonomy, leading to profound cultural confusion.

Our modern world has sought to replace the true story with an artificial story that denies the full humanity of God’s image bearers and crumbles beneath the biblical narrative and faith expression of those whose citizens weren’t stained by the Enlightenment’s fallout.

The Enlightenment was a distortion of Christianity. It reshaped the Christian story, gutting it of its divine authority, public truth, and supernatural reality. In its place, it enthroned reason, progress, and human autonomy, setting the trajectory for deep cultural confusion.

In our modern world, this artificial partition continues to obscure the true one. It has successfully confused many Christians who continue to see their identity, not through the lens of God’s story, but through syncretizing the Enlightenment’s dirty lenses of progress.

Nevertheless, this counterfeit partition collapses under the weight of the biblical story and the lived faith of those untouched by the Enlightenment’s fallout.

Every story has consequences, and the Enlightenment is no different. Whenever a culture embraces a false story, it will inevitably be shaped by that story—not just as individuals but as an entire society.

The Enlightenment’s view of limitless progress, detached from divine authority, has led to massive moral confusion. Without a transcendent anchor to hold it, truth becomes susceptible to whatever cultural forces desire it to be. Freedom is no longer about living within God’s design but about asserting autonomy from God at any cost.

The question before us is this: Will we continue to live by the Enlightenment’s artificial story and partition, one that leads to distortion, fragmentation, and dehumanization? Or will we return to, embrace, and enact the true story of the whole world that tells not only of God and his kingdom but shows us our place within it—a story that offers coherence, purpose, and ultimate restoration?

The Enlightenment didn’t just reshape culture—it reshaped our theology and our understanding of how we live in and engage the world. With reason and human autonomy exalted to such a lofty place, the church faced a choice—remain anchored in the biblical story and perhaps be cast aside and disregarded as irrelevant, or reinterpret the gospel to fit the changing intellectual climate?

Next week, we’ll explore how this tectonic shift gave rise to liberal theology and birthed a movement that sought relevance—but in the process, redefined the gospel itself.

James Davison Hunter, To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 75.

Michael W. Goheen and Craig G. Bartholomew, Living at the Crossroads: An Introduction to Christian Worldview (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 68.

Hunter, 9.

Goheen and Bartholomew, 68.