Do you remember the first time you heard the gospel? Was it from a pulpit, at Vacation Bible School, in Sunday School, on television, at a conference, or maybe at a camp? What exactly did you hear? What were the key elements of that presentation?

Most of us grew up with some version of a gospel presentation. After becoming a Christian, you were likely taught a simple way to share your faith—something easy to memorize and pass along. For me, a few approaches stuck, but the one I remember best is the ABCs of the gospel:

A – Admit you are a sinner.

B – Believe that Jesus died for your sins.

C – Confess that Jesus is Lord.

Simple enough, right? Maybe your experience was a bit different. If you were part of a college ministry, you might have encountered the Four Spiritual Laws:

-

God loves you and has a wonderful plan for your life.

-

Man is sinful and separated from God. Therefore, he cannot know and experience God’s love and plan for his life.

-

Jesus Christ is God’s only provision for man’s sin. Through him, you can know and experience God’s love and plan for your life.

-

We must individually receive Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord; then we can know and experience God’s love and plan for our lives.

That’s a well-known and widely used presentation. But perhaps you learned something more in-depth, like the Romans Road. This method goes beyond the ABCs or the Four Spiritual Laws, addressing five major points from the book of Romans. It doesn’t just stop at accepting Christ; it assures believers of their salvation:

1. The Problem of Sin

Romans 3:23 — “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.”

This verse highlights the universal reality of sin. Every person falls short of God’s standard.

2. The Consequence of Sin

Romans 6:23 — “For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Sin results in spiritual death and separation from God, but God offers eternal life through Jesus.

3. God’s Provision Through Jesus

Romans 5:8 — “But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.”

God’s love is shown through Jesus’ sacrificial death.

4. The Response of Faith

Romans 10:9 — “If you declare with your mouth, ‘Jesus is Lord,’ and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.”

Salvation comes by confessing Jesus as Lord and believing in his resurrection.

5. The Assurance of Salvation

Romans 10:13 — “For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.”

Everyone who turns to God in repentance and faith is assured of salvation.

It’s incredible how God has used these methods to bring people to saving faith in Christ.

There are so many more methods—Evangelism Explosion (EE) began with a diagnostic question, “If you were to die today, do you know for sure that you would go to heaven?”

The Bridge Illustration had the presenter draw a picture, and the same goes for the Three Circle method.

Each gospel presentation attempts to help people understand the good news of Jesus Christ—which is very good. However, each one is somewhat limited in what it conveys. They each assume a certain knowledge of God—a belief that God exists, that there is only one God, that heaven exists, and that a person knows what sin is. They are fantastic in speaking to someone who already has an awareness of basic Christian theology, but what if someone doesn’t? In our increasingly pluralistic world, such truths can’t be assumed anymore.

Over the years, after meeting Christians from around the world, I’ve often wondered why God didn’t simply give us a universal three-, four-, or five-point gospel outline. Why didn’t Jesus or Paul present it that way? Have you ever considered that?

The Start of the Formula

We often rely on formulas to simplify complex problems in math and physics. But what happens when we apply that same mindset to the gospel? While formulas can bring clarity, they risk oversimplifying the profound and transformative nature of the good news and the theological foundation upon which it rests.1 It’s essential to understand the key elements of the gospel but relying on the reduction of a step-by-step presentation can have unintended consequences.

I’m not suggesting we abandon clear gospel formulations, I believe that it is very good to have the basics down in an understandable format that can be easily communicated.

Instead, I want to examine how and why these formulaic presentations were created, how they’ve influenced our understanding of the gospel, and how we can reclaim a more comprehensive and vibrant view of the good news.

Interestingly, structured gospel presentations didn’t emerge until the time of George Whitefield and John Wesley. Their method was quite straightforward:

-

Your sin

-

Christ’s sacrifice

-

Your response

That’s pretty good. Simple to replicate. Easy to remember. But is it enough?

Here’s what I mean. In the premodern era, the gospel was embedded in sermons, liturgies, creeds, confessions, and catechisms. People were shaped by the truth of the gospel through prolonged exposure over time. There were no standardized, step-by-step presentations. It wasn’t until the late 18th century that structured approaches emerged, further refined in the 19th century, and reaching their most recognizable form in the mid-20th century.

But why didn’t God reduce the gospel to a neat set of points? And who decides what belongs in a gospel presentation — and what gets left out? An even more important question is this: how did Jesus’ audience understand the gospel?

While these formulas attempt to present a clear and simple message rooted in Scripture, they often reduce the gospel to a personal transaction — a way to “get saved” and avoid punishment. I’ve lost count of how many people have stopped me mid-conversation to assure me they’re already “saved.” Inevitably, I ask how and why they came to that belief. For most, it’s because they prayed a prayer as a child, accepted Jesus into their heart, or were baptized.

But here’s the hard part — many of these same people show no evidence of a transformed life. They live in ongoing sin, show no repentance, and have little to no desire for God. Yet they cling to the belief that their salvation is secure.

This mindset is pervasive in evangelicalism, and it doesn’t take long to uncover the root problem: a distorted understanding of the gospel, shaped by bad theology. When salvation is reduced to a formula, it’s no surprise that the fruit of genuine faith is absent.

Often absent in gospel presentations are the truths of the kingdom of God, the call to discipleship, and the invitation to join God’s mission in the world. These are deemed to be extra and unessential for salvation. The message is stripped down, repackaged for quick understanding, and often presented as something to be accepted rather than a transformative story to be lived.

Over the years, I’ve spoken in many different settings, and whenever I bring up this topic, I notice people squirm in their seats, with confusion quickly taking over their expressions. They’ve never stopped to consider what they truly believe or how they came to believe it. Instead, they simply accept it as true and expect me to repeat what they’ve been taught by others. But that’s the issue—they’ve accepted and passed on something much less than what the Bible actually presents.

My evangelist friends are the most uncomfortable. They fear I’m needlessly complicating the gospel or diminishing the urgency of sharing it. But far be it from me to discourage evangelistic zeal! I long for people to come to the saving knowledge of Jesus Christ and have no objection to using clear gospel presentations. I think that we need more evangelism not less!

My concern is that without an understanding of exactly what we are communicating, we risk making converts and not disciples, and in doing so, risk a similar rebuke that Jesus gave in Matthew 23:15,

“Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you travel across sea and land to make a single proselyte, and when he becomes a proselyte, you make him twice as much a child of hell as yourselves.”

In my view, one of the greatest challenges the church faces today is gospel reduction. While our desire for simple gospel presentations is good, they can have serious negative consequences.

John Stott once overheard a conversation between two pastors discussing what they called “an irreducible minimum gospel.” He dismissed the idea, responding, “Who wants an irreducible minimum gospel? I want the full, biblical gospel.” I share his frustration, but I’ve found that many evangelicals don’t. They prefer to simplify it into three to five points, creating a quick plan of salvation. But the truth is, the gospel is so much more than that simply a plan of salvation. It is not less than that, but it is so much more.

So why did these gospel presentations become necessary? Where did they come from?

In short, they are a product of modernity.

The Subtle Undercurrents

For many of us, the term “postmodernity” is familiar, but “modernity” often fades from view. Think of postmodernity like the latest installment in the Star Wars franchise—it grabs our attention. Meanwhile, modernity is like Disney, the company that owns and shapes it from behind the scenes.

So, what is modernity? It refers to the cultural ethos that emerged from the late 16th and 17th centuries and still influences us today.2 Modernity is like an ocean current, carrying us along unconsciously—much like the East Australian Current (EAC) in Finding Nemo.

Modernity and postmodernity are intertwined, sharing foundational beliefs while expressing themselves differently. Picture them as a parent and child who share DNA and family history, yet each is shaped by the ideas of their respective time. While some argue that we remain within modernity, others suggest we have fully entered postmodernity, or perhaps even a new, unnamed era. Regardless of the terminology, the underlying influence of modernity remains, providing the foundation upon which postmodernity rests. To grasp the present, we must first understand modernity.

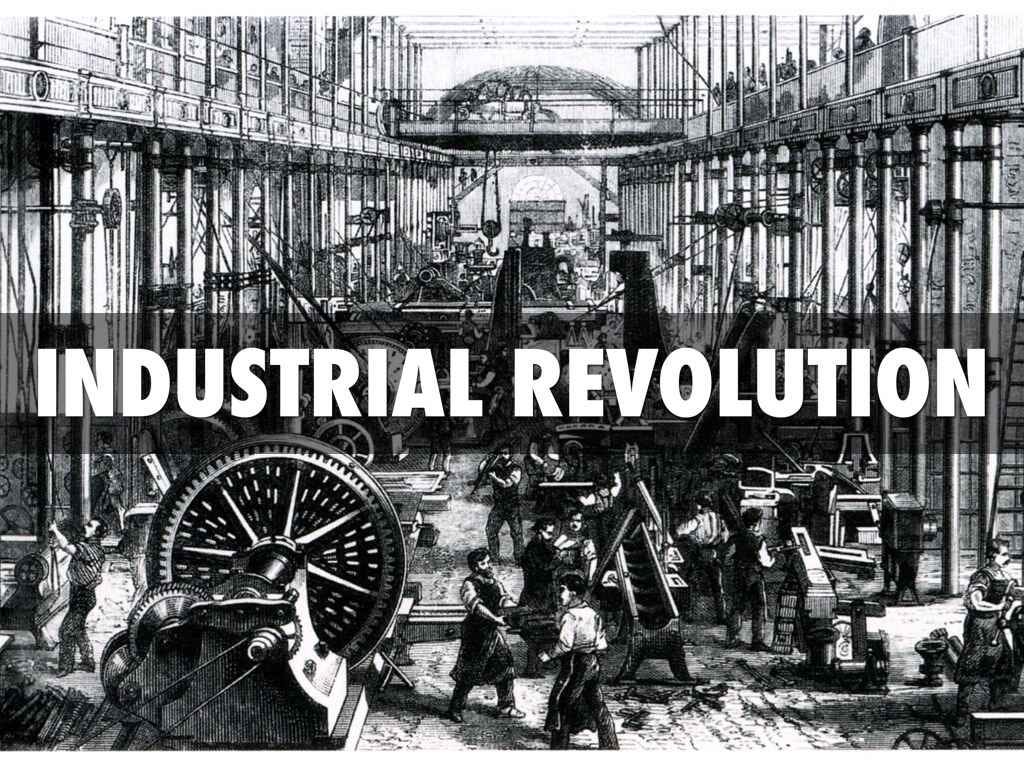

The subtle undercurrents of modernity began in the 16th and 17th centuries, but they surged into prominence with the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. Fueled by technological innovation, capitalism, urbanization, and telecommunications, modernity swept across the cultural landscape like a tsunami. Religious belief, long the dominant worldview, was now over by the waves of industrial progress.3 No individual, institution, or culture—including the church of Jesus Christ—escaped its effects.

Modernity is often described as a condition and a state of mind, characterized by the elevation of human reason over divine revelation, individual autonomy over communal responsibility, and scientific progress over religious belief. It is so embedded in our society that it feels like the air we breathe. It shapes how we understand meaning, value, identity, purpose, and our place in the world.

Like a tsunami reshaping the coastline, modernity fragmented religious belief. The Christian faith was repackaged to align with the values of the industrial age—an age that prized mass production, efficiency, and standardization. The gospel was commodified, measured not by the formation of lifelong disciples but by numerical conversions. Salvation, once understood as a holistic journey of justification and sanctification, was reduced to a single moment of decision. Reflecting this mindset, gospel presentations became formulaic—efficient, standardized, and reproducible.

The theologian David F. Wells sheds light on this transformation by distinguishing between modernization and modernity. While modernization refers to the external changes brought about by industrial progress, modernity refers to the internal shifts in values and beliefs that accompany these changes. As Wells notes:

“…I [distinguish] between modernization and modernity, two forces that together are driving the revolutionary transformation of our world. The former is producing changes it the outer fabric of our life; the latter is altering the values and meanings that emerge from within the context of the modernized world—values and meanings that in the modern context seem altogether normal and natural.”4

These meanings created a belief structure that seems completely normal and natural, but upon closer inspection is anything but. How did modernity and modernization do that? What exactly did it do to our understanding of the gospel? Let’s explore that next.

The Reshaping of the Gospel Shoreline

In the West, the waves of modernity and modernization have dramatically reshaped our understanding of Christianity, reducing the gospel and changing its shoreline.

#1. The gospel was reduced to information, not transformation.

With the barriers of religious authority washed over by the tsunami, Christianity had to adapt. Modernity’s demand for empirical evidence led Christianity to shift toward rational arguments, as miracles couldn’t be proven by its standards. Though the early church used intellectual arguments, modernity demanded Christianity prove the gospel’s reasonableness within its framework. In the process, the supernatural elements—the miracles and divine revelations of Scripture—were often downplayed because they couldn’t be empirically substantiated. While this rational defense was understandable, it ultimately reduced Christianity to an assent of logical arguments and moral systems.

#2. The gospel was separated from its greater storyline.

Rather than presenting the gospel as part of the Bible’s grand narrative, it was stripped from its broader context — like spotlighting one chapter and mistaking it for the entire book. This fragmented approach led to widespread confusion about Christianity’s role in public life.5

As telecommunications advanced and mobility increased, people became less tied to specific places and communities of faith. Along with the greater freedom that modernity promised, time became further segmented with greater opportunities and choices for how time would be spent, meaning more competition for time. In response, the gospel was reshaped to fit the values of modernity’s “lesser gods” — mass production, efficiency, and standardization. The result? A further reduction of the gospel’s transformative and all-encompassing nature.

#3. The supernatural was suffocated.

Modernity, with its emphasis on reason, science, and empirical evidence, offered little room for the supernatural. As everything became more controlled and defined, miracles and divine acts like the virgin birth, resurrection, and ascension were dismissed as relics of superstition and myth.

The gospel, already reduced to a mere intellectual argument, was stripped of its supernatural essence. Without room for the miraculous, it was no longer seen as a living, transformative reality — only a philosophy to be debated rather than a power to be experienced.

#3. The gospel became restricted to the private sphere.

With the gospel being removed from the greater storyline and supernaturalism suffocated in the public square, Christianity retreated into the private sphere. At the same time, Christianity was being assaulted from the inside as liberal theology was finding a voice. Both liberal theology and modernity forced Christianity to retreat further from public life, further stripping Christianity of its cosmic nature resulting in a focus on personal salvation and moral improvement, retreating from broader cultural and societal conversations.

The result was that Christianity became primarily an individualistic pursuit, with less emphasis on cultural idols or addressing systemic injustice. Once an influential voice in the public square, the church was muted, leaving secular ideologies to shape public life.6

#4. The gospel became reduced to justification and heaven.

Already confined to the private sphere, the gospel adapted by advocating for a solely spiritual kingdom. Faced with mass production, standardization, and the demand for efficiency, Christianity’s message became simplified and streamlined. This reduction led to a focus on justification alone, emphasizing the initial salvation event over the ongoing process of sanctification. As a result, the gospel was often presented not in its full theological depth of justification, sanctification, and glorification, but primarily as a justification-only salvation, leaving the transformation of the believer and the church’s role in the world largely unaddressed.

#5. The gospel became individual at the cost of the communal and relational.

Once salvation was reduced to justification alone and getting a person into heaven, the church was sidelined—rendered unnecessary at worst and secondary at best. With the focus solely on individual salvation and the afterlife, the church was no longer a community for discipleship, spiritual formation, and public witness. This shift further diminished the gospel and distorted the church’s role in the world to be a living representation of God’s kingdom on earth.

#6. The gospel was reduced to sin management.

With the storyline of creation, fall, redemption, and restoration removed, the kingdom of God became divested, the mission truncated, and the prophetic voice silenced, there was little left for the church to focus on except keeping sin in check. The grand narrative of God’s redemptive work in the world was replaced with an individualistic pursuit of personal salvation. Without the cultural mandate to shape society or a clear mission to engage the world with the gospel, the church became exclusively inward-focused, preoccupied with moral behavior rather than transformation in the public sphere. As a result, the church lost its prophetic edge, failing to speak and even acknowledge systemic injustice, challenge idols in society, or call the world to the broader kingdom vision of God’s reign over all creation.

#7. The gospel was recalibrated as therapy.

Perhaps the greatest fallout of the gospel is the most appalling. The gospel is incredibly awesome with God entering the world through Christ to save man and restore creation, but as the waves of modernity crashed upon it, it became something altogether different—smaller and removed. Rather than the glorious all-encompassing gospel, it had become a form of therapy—offering a better life of happiness and personal comfort for anyone willing to come.7

The therapeutic gospel is reminiscent of the return of the Jewish exiles when they saw the foundations of the new Temple. The younger generation who had never seen the Temple rejoiced, but the older generation wept because it was so much less than what was before.

“But many of the priests and Levites and heads of fathers’ houses, old men who had seen the first house, wept with a loud voice when they saw the foundation of this house being laid, though many shouted aloud for joy, so that the people could not distinguish the sound of the joyful shout from the sound of the people’s weeping. For the people shouted with a great shout, and the sound was heard far away”—Ezra 3:12-13.

With the two Temples contrasted with one another, the new Temple is a far cry from the first, further amplifying the loss. The new Temple lacked the grandeur, splendor, and transformative vision of the original. Where once the gospel was the cosmic story of redemption, bringing the fullness of God’s kingdom to bear on the world, it has become a shadow, a shallow substitute and reminder of what once was. Nevertheless, God will still be proven true, even though every man will be a liar.

The therapeutic gospel, not without some truth, has been distorted and distilled into a self-help tool for personal happiness, stripped of the scope of its mission. The therapeutic gospel seeks to comfort rather than confront, to affirm rather than transform. The true gospel calls us into something altogether different and much greater—an invitation to participate in God’s redemptive mission to the world, to be transformed, and to live with purpose—agents of restoration in the world that are prepared to love, listen, serve, share, sacrifice, suffer, and if necessary, die.

#8. The gospel became commodified.

With the principles of modernity in place and the Industrial Revolution in full swing, it was a matter of time before the gospel became a product itself that could be bought and sold for a specific benefit such as personal happiness, success, or self-improvement. This further led to a shallow understanding of the gospel, where its true meaning and purpose (the Kingdom of God, reconciliation, restoration, and God’s glory) become further obscured by the promises of personal benefits and outcomes.

#9. The gospel became commercialized.

The final reshaping of the gospel is no less appalling than when the gospel became a form of therapy. The big three of the industrial revolution (mass production, efficiency, and standardization) are intimately connected to capitalism. Capitalism, in its desire to maximize profit, further reduced the gospel.

Once, Christian leaders, misled in their understanding of evangelism, sought to draw large crowds for the sake of reaching as many people as possible. But often, their motivations went beyond genuine outreach; they were also driven by a desire to increase their own status, expand their influence, or build their personal following. In this approach, evangelism became less about faithful proclamation of the gospel and more about numbers, success, and recognition. Unfortunately, this mindset led to shallow conversions and a distorted view of discipleship, where the focus shifted from transformed lives to visible results and measurable growth.

In doing so, the gospel was reduced to a product. Preachers and churches began to sell their particular slant on the gospel, appealing to mass crowds with the offer of success, comfort, and personal happiness. Worship services became performances, platforms became stages and the gospel was stripped of its confrontative nature and was packaged to appeal to and fit into modern cultural sensitivities, preferences, and schedules. Offerings became marketed like entertainment options. The emphasis on the communal nature of the gospel shifted to individualistic consumption with the worship experience. Customers were encouraged to “buy into” the gospel for personal benefit rather than live out the counter-cultural implications.

In this environment, the role of the pastor shifted from that of a spiritual guide to that of a CEO or an attractional, charismatic personality. Under this model, the gospel ceases to be a life-changing proclamation of God’s kingdom and instead becomes a product to be bought into—a theological version of multi-level marketing, designed to recruit disciples and sustain the cycle, as the church prioritizes profits over true transformation.

As the gospel became commercialized, it lost its prophetic call to challenge, convict, and transform. In its place was a gospel of personal enhancement, with a focus on what people could gain from it rather than what they were being called to give.

Like the once glorious Jewish Temple that was meant to give hope to the broken, it was reduced to nothing more than a transaction, where salvation was seen less as a gift to be received with gratitude and obedience and more as a product to be acquired for individual benefit. This tragic shift left the gospel and theology denuded, disconnected from its true purpose of glorifying God and advancing his mission in the world.

The Missioholistic Approach: A Restoration of the Gospel And A Way Forward

Modernity has seriously malformed how we see and understand the gospel—reshaping it into something less than it is. Nevertheless, God is still on the throne and his mission will be accomplished.

For many wishing to move the church forward and see the genuine spiritual transformation that transcends socio-economic, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds, much of the knowledge and heart is already there—what is needed is a better framework for applying it. That’s where the Missioholistic approach comes in.

The Missioholistic approach corrects the distortions modernity has introduced to the gospel, by addressing several key areas:

#1. Holistic Transformation: The gospel is not simply about intellectual assent, but about the radical transformation of individuals and communities through the Spirit as they live in the kingdom now. Missioholism helps construct countercultural practices that create shalom in the home, our work, our leisure, and the digital sphere.

#2. Greater Story: The gospel is restored to its rightful place within God’s unfolding narrative of creation, fall, redemption, and restoration and frames our mission and engagement with the world. The greater story becomes the framework within which our mission is understood.

#3. Supernatural Reality: The gospel is supernatural, and missioholism affirms the Spirit’s active role in transformation, the unseen realm, and the reality of the spiritual powers at work in the world. Rather than having a closed system of the natural world, missioholism recognizes the flesh, the world, and the spiritual powers working together.

#4. Public Engagement: Missioholism sees Christ’s supremacy in all of life and refuses to allow faith to be confined to the private sphere. It is a public truth that calls believers to engage in culture and embody kingdom virtues in every sphere of society. Missioholism provides the biblical principles of cultural engagement in a post-Christian pluralistic world to establish gospel credibility, fulfill our purpose within the cultural mandate, challenge cultural idolatries with wisdom and grace, win the lost, and bring glory to God.

#5. Missional Church: The church is not a destination focused on institutional survival, but a sent people to convey Christ’s Lordship in the world in thought, word, and deed. Missioholism provides the framework to engage faithfully while maintaining a distinct identity as the new creation that serves as an apologetic to the world and a testimony to the spiritual powers of their demise.

Conclusion

The Missioholistic approach is just that—an approach. It is not the only one, but it is one that has equipped Christians to live faithfully and minister effectively while nurturing holistic health in every aspect of life.

Having pastored for over 20 years in urban and suburban centers across the Midwest and New England, I’ve witnessed firsthand how the Missioholistic approach has brought renewal to ordinary churches. These were churches in blighted communities, often without significant networks or resources—just everyday people committed to loving God, loving others, and holding fast to the Word of Truth. They prayed, fasted, worshiped, wept, and cared. They engaged in the rhythms of daily life, and through their faithfulness, God worked powerfully, drawing people from across the world into the church.

The Missioholistic approach is not a quick fix or a magic bullet. Rather, it is a framework that empowers ordinary Christians to resist the cultural idols surrounding them while reaching out to those desperately in need of Christ’s love. The churches that embraced this approach didn’t know it by name, but they lived it. I simply guided them to pray, proclaim the Word of life, and see life and ministry from a new perspective.

I wish I could say the process was instantaneous, but it wasn’t. It was difficult, and the changes in the churches came slowly. I failed repeatedly. There were times I felt distracted, depressed, and overwhelmed, yet I kept showing up. Despite my weaknesses, God still worked. But his work was often subtle, unfolding in small, almost imperceptible ways. Relationships were built, and lives were transformed through the steady, small acts of obedience that accumulated over time.

You can do the same—that’s the beauty of it. Missioholism recognizes the pervasive power of sin while emphasizing the necessity of meaningful relationships. It keeps the church community central, ensuring no one stands alone and that the gospel is both lived and proclaimed in everyday life. The gospel is more than a formula—it is a brand-new way of life. Modernity has inflicted immense harm upon the gospel and the church, but God’s kingdom presses forward—and we can live in that reality.

Join me next week as I explore the disobedient child of modernity—postmodernism—and examine how it reshaped the gospel.

David F. Wells, No Place for Truth: Or Whatever Happened to Evangelical Theology? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993), 7.

D. A. Carson, The Gagging of God: Christianity Confronts Pluralism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 20.

David F. Wells, God in the Wasteland: The Reality of Truth in a World of Fading Dreams (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 7, 61.

Wells, God in the Wasteland, 7.

Craig G. Bartholomew and Michael W. Goheen, The Drama of Scripture, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2024), xxiv.

Wells, God in the Wasteland, 27.

Wells, No Place for Truth, 6.