This topic will be covered in six parts. This is part 6. Check out

Weighed and Wanting

Over the past five weeks, we have examined Christian nationalism and its claims.

We looked at the seeds that enabled it to happen culturally and psychologically—a continued marginalization and exclusion from public life, especially in the sexual and parenting arena.

We examined it biblically and theologically according to its own stated goals, framework, and intent, laying it alongside the Scriptures to see if it truly aligns with what Scripture teaches.

We have examined it historically to evaluate its claim that America was founded as a Christian nation.

We examined it missiologically to see if Christian nationalism is an accurate expansion of the gospel, as Christ intended.

We have examined Christian nationalism using insights from neuroscience and neurotheology to discern whether it reflects the work of God, particularly in its capacity to form people who love their enemies as Christ calls us to.

After using these five criteria, it has become readily apparent that Christian nationalism has failed on all five fronts.

It is not Christianity, but a perversion of the gospel.

The Questions That Need to Be Answered

Evaluating and critiquing is one thing, but coming up with an alternative is something altogether different. In light of that, we have a series of questions that should be answered:

-

What is the alternative to Christian nationalism?

-

How can we cultivate proper patriotism?

-

Is it wrong to love one’s country and want its best?

-

What are the criteria to discern whether or not patriotism has become syncretistic?

-

Is it wrong to want to advocate a certain kind of morality and public virtue?

Historically, Christians have varied across the spectrum in their approach to political and civic engagement, ranging from those who advocate for complete withdrawal (e.g., the Amish) to those who completely engage (e.g., the Moral Majority).

Wanting a Christian politic is a very good thing, as is wanting society to flourish and a kind of civic virtue. It is not wrong to love your country and want its best. It’s not wrong to love your flag and want to defend your country. But it is wrong to make that supreme; when that happens, then it becomes idolatrous.

That’s the issue—how can our patriotism be cultivated in a way that honors God but does not creep into idolatry?

To do this faithfully, we must consider several key factors:

-

The message we are proclaiming (both explicitly and implicitly)

-

The means we employ to communicate it (including how we understand and express our patriotism)

-

The posture we adopt (our disposition reveals a great deal about our hearts),

-

The power we are willing to use (or refrain from using)

-

The pain we are prepared to endure for the sake of Christ.

Before we go any further, the overarching principle guiding our discussion must be this: Are we using the gospel as God intended, or are we instrumentalizing it for some other purpose? The gospel must never be treated as a tool to advance any agenda—whether for our nation, reputation, or cause—but rather treasured for what it truly is: the revelation of God’s power and grace in the person and work of Christ Himself.

The Message We Are Communicating

What is the gospel we’re proclaiming? For many of us, “gospel” is a given, however it is anything but. In Mark 1:14-15 we read,

14 Now after John was arrested, Jesus came into Galilee, proclaiming the gospel of God, 15 and saying, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel.”

The question is simple—what is the “gospel” if Jesus hadn’t died yet? This is not an isolated verse, but is found throughout the four gospels—each one articulating that the “gospel” is being preached (Matthew 4:23; 9:35; 26:13; et al.).

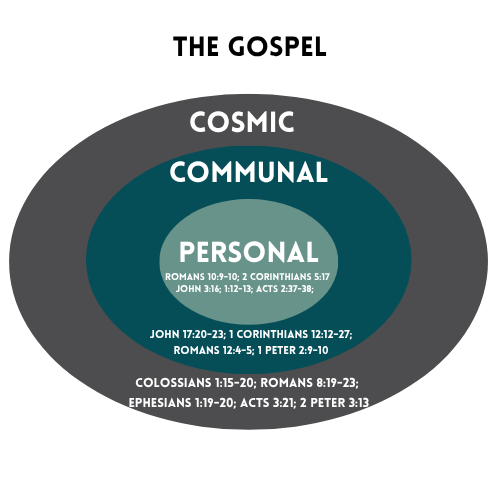

Of course, we know that the gospel is good news. But good news of what? To be saved from sins? Yes. But there is more to it, because if we are to be logically consistent, the definition we employ has to include what Jesus meant by it. Therefore, in light of that, we define gospel as follows,

The gospel is the good news that God, through the life, death, resurrection, ascension, and reign of Jesus Christ—the Christ event—has fulfilled His covenant promises to redeem a fallen humanity from sin and restore creation. Through grace, this message calls individuals and communities to respond in faith, be reconciled to God, and participate in God’s mission of establishing His kingdom on earth as it is in heaven. The gospel reveals a kingdom that is both already inaugurated and not yet fully realized, empowering believers by the Holy Spirit to live as God’s renewed people in hopeful anticipation of the new creation.

Whenever we hear the term “gospel,” this is the meaning behind it. However, most contemporary expressions of the gospel refer to only one part of it—the reconciling of humanity to Himself through Christ, and fail to encapsulate the other elements, which leads to a malformed discipleship and confusing cultural engagement.

That being said, Christian nationalism takes into consideration the other aspects—establishing His kingdom on earth as it is in heaven. So they have the message right, but it is the means that they employ to accomplish that message that is where the problems start.

The Means by Which We Communicate It

The message of Jesus must incorporate the means of Jesus—His birth, life, death, resurrection, and ascension. In our hyper-reductionistic, justification-only salvation, we fail to take into consideration the ways of Christ. As Russell Moore has stated repeatedly—

“Multiple pastors tell me essentially the same story about quoting the Sermon on the Mount parenthetically in their preaching—‘turn the other cheek’—to have someone come up and say, ‘Where did you get those liberal talking points?’

He adds:

‘What was alarming to me is that in most of these scenarios, when the pastor would say, “I’m literally quoting Jesus Christ,” the response would not be, “I apologize.” The response would be, “Yes, but that doesn’t work anymore. That’s weak.” When we get to the point where the teachings of Jesus himself are seen as subversive to us, then we’re in a crisis.’”1

The message of Jesus must be understood in the context of His whole life. Every aspect of Jesus’ life is essential to accomplishing our salvation, yet many contemporary gospel presentations tend to overlook key details. We often hear about His birth at Christmas and His death at Easter, but His ascension is rarely mentioned—unless we’re part of a liturgical tradition.

So, what significance does the ascension hold? While His death and resurrection are well-known, what about His miraculous birth and perfect life? Without the incarnation, Jesus is merely a martyr; the resurrection alone doesn’t make sense apart from the crucifixion and the incarnation. And the ascension? It’s crucial for establishing His enthronement as King. Each of these pivotal moments in the Christ event shapes the contours of Jesus’ qualification to bring us salvation and usher in His kingdom. Let’s explore each one in turn.

Jesus’ Event

Jesus’ birth

Jesus’ birth is essential not only because it fulfills numerous prophecies, but because it reveals that He is both fully God and fully man—an essential truth for establishing the link by which our sin can be atoned for.

Let me illustrate why this is so significant.

When we sin, the penalty corresponds to both the offense and the authority of the one offended.

For example, if I were to punch a homeless man, the consequences would likely be minimal. But if I punched a police officer, the punishment would be far greater—because I’m not merely attacking a person, but the authority and justice they represent.

Now, imagine if I punched the mayor of Chicago. My crime would not only affect the mayor but also symbolically strike the entire city, resulting in a heavier penalty. Take it further—if I punched the President of the United States, the consequences would be even more severe, as I would be attacking the office that represents an entire nation.

Sin against God is infinitely more serious.

At its core, sin is a rejection of God’s authority, a declaration saying, “I don’t need You, and I won’t obey You.”

The penalty must be proportional to who God is—an infinite and eternal being, the Creator, the very embodiment of justice, mercy, and love.

Therefore, the penalty for sin against God is infinite and eternal.

This leads to a vital conclusion: only one who is both infinite and fully human could pay this penalty—someone who can bear the infinite weight of God’s justice while fully identifying with humanity.

Jesus alone fits this description.

As the God-man, He absorbed the full weight of God’s justice and offered Himself as the perfect, once-for-all sacrifice for humanity. That’s why the incarnation is central to understanding His qualification to save us.

Jesus’ life

Jesus lived a perfect, sinless life (Hebrews 4:15), and this was essential. He needed to fully identify with us—not only in our humanity but in our experience of temptation and struggle—while remaining without sin. This identification is also evident in moments like His baptism, where He took on the fullness of human experience.

Some might ask, “If we are sinful creatures, how could Jesus truly identify with us without sharing in our sinfulness?”

C.S. Lewis offers a phenomenal insight into this,

“A silly idea is current that good people do not know what temptation means. This is an obvious lie. Only those who try to resist temptation know how strong it is. After all, you find out the strength of the German army by fighting against it, not by giving in. You find out the strength of a wind by trying to walk against it, not by lying down. A man who gives in to temptation after five minutes simply does not know what it would have been like an hour later. That is why bad people, in one sense, know very little about badness. They have lived a sheltered life by always giving in. We never find out the strength of the evil impulse inside us until we try to fight it: and Christ, because He was the only man who never yielded to temptation, is also the only man who knows to the full what temptation means—the only complete realist.”2

Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Jesus’ death and resurrection are the most well-known parts of His life and mission. The Gospels devote the majority of their attention to the final three years of His ministry, with a significant focus on the final week. It was on the cross that Jesus paid the price for our sins, but it was His incarnation and sinless life that made His death and resurrection effective and victorious.

As Martin Luther once said, the resurrection is the hinge upon which the door of Christianity turns. It’s no surprise, then, that the early church didn’t initially celebrate Christmas. They were wary of resembling Roman customs, especially the birthday celebrations of Caesars, who claimed divine status. Instead, their focus was on the resurrection, which was the definitive proof of Jesus’ identity and the foundation of their hope.

Jesus’ ascension

Yet perhaps the most neglected part of Jesus’ life is His ascension. And that’s a problem—because the ascension isn’t an afterthought; it’s the climactic enthronement of the King.

These are each key for understanding salvation and what it means to live in light of His already/not yet kingdom.

Jesus’ event.

The Jesus event—His birth, life, death, resurrection, and ascension—reveals both who Jesus is and why He came. He came to..

-

Reveal God and fulfill His will (John 6:38; 1:18)

-

Save sinners (Luke 19:10; 1 Timothy 1:15; Mark 2:17)

-

Give His life as a ransom (Mark 10:45)

-

Bring the Kingdom of God (Mark 1:14–15)

-

Destroy the works of the devil (1 John 3:8),

-

Bring light, truth, and abundant life (John 10:10; 12:46; 18:37).

In light of His mission, we are called to make disciples using the methods He modeled—above all, love. We are to…

-

Love God (John 14:15)

-

Love one another (John 13:34-35)

-

Love our enemies (Matthew 5:43-45).

Jesus not only taught us how to live (Matthew 5–7) but commanded us to teach others to obey everything He taught (Matthew 28:18-20).

This way of life includes:

-

Loving others (John 13:34–35)

-

Serving others (Mark 10:43–45)

-

Sacrificing willingly (Luke 14:27–33)

-

Denying ourselves (Luke 9:23)

-

And refusing to advance the gospel through violence (Matthew 26:52)

Scripture is clear: God is not merely concerned with outward obedience, but with the condition of the heart (1 Samuel 16:7; Isaiah 29:13; Psalm 51:16–17). True discipleship flows from inward transformation empowered by the Spirit, not mere external compliance.

The Parameters of Our Patriotism

Now that we’ve established the message we are communicating—the gospel of the Kingdom—and the means by which we may communicate it, we must go deeper into what it looks like to engage faithfully as citizens of an earthly kingdom.

Our primary allegiance is to our heavenly citizenship (Philippians 3:20). Yet we also hold earthly citizenship, and the most biblically instructive model we have is that of the apostle Paul, who was born a citizen of the Roman Empire (Acts 22:28).

How did Paul use his Roman citizenship?

-

To protect himself from unlawful punishment (Acts 22:25–29)

-

To secure a fair trial (Acts 25:10–20)

-

To advance the gospel, even amid suffering (Acts 28; Philippians 1:12–13)

Notice that Paul operated within the bounds of the law, and in doing so, his trials became a public platform for proclaiming Christ. He didn’t idolize his citizenship, but he stewarded it wisely to serve the mission of God.

How, then, do we engage in our context?

As citizens of a constitutional republic and representative democracy, we must ask: What does faithful, biblical patriotism look like for followers of Jesus? What guidance does Scripture provide?

While we draw wisdom from both the Old and New Testaments, our emphasis is on the New Testament, where Jesus makes clear that His Kingdom is not to be identified with any earthly nation—including the nation-state of Israel (John 18:36). Some practices permitted or commanded under the old covenant, such as holy war, are not normative for the church today, which is a transnational, Spirit-formed people called to embody the way of the cross. The New Testament sets the pattern for how we live as citizens of heaven while faithfully engaging in the kingdoms of earth.

The Church: A Political Witness of Another Kind

Though not partisan, the church is deeply political in the biblical sense: it is a visible, public community that lives under the reign of King Jesus. The local church is an outpost of that Kingdom, showing the world an alternative politic—one shaped by grace, justice, reconciliation, humility, and truth. A person who claims Christ and who advocates for Christianity to be instrumentalized at a national level without being engaged in the local church is not fulfilling the role of a Christian.

As Christians, we must hold together the insights of Romans 13 (that government is God-ordained) and Revelation 13 (that governments can become beastly when they demand ultimate loyalty). These two passages remind us to be grateful for the state’s role in restraining evil while also recognizing its limitations and dangers.

We also must remember that our ultimate hope is not in America—or any other nation—becoming great. Our hope is in the unshakable Kingdom of God, inaugurated through the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ.

We live faithfully now, not to gain power, but to bear witness. Not to take control, but to serve as salt and light.

We are citizens here, yes—but we are ambassadors of another Kingdom (2 Corinthians 5:20), one that is already here and is yet to come.

What then do we do?

-

We pray for our leaders, the nation, and justice to prevail (1 Timothy 2:1–2).

-

We honor governing authorities, even when they are unjust (1 Peter 2:17), while obeying God over man when the two are in conflict (Acts 5:29).

-

We familiarize ourselves with how our government works, and we understand our rights and responsibilities under it.

-

We stay informed about local, state, and national issues—not out of fear, but out of wisdom.

-

We uphold the principle of subsidiarity—that decisions should be made at the most local level capable of addressing them (families, churches, communities, local and state governments).

-

We serve on local boards, school committees, and civic groups.

-

We volunteer with organizations that support justice, care for the vulnerable, and seek the flourishing of our communities

-

We encourage critical thinking rather than partisan tribalism, making sure our loyalty is to the truth, because all truth is God’s truth, regardless of party or political ideology.

-

We speak out against injustice, corruption, and policies that harm the common good (Proverbs 31:8–9).

-

We pay taxes (Romans 13:7) and fulfill civic duties with integrity.

-

We may defend our country if called upon to do so in just and lawful ways (Luke 3:14; Romans 13:4).

-

We do not use violence to expand the kingdom of God (Matthew 26:52; John 18:36).

-

We may engage in peaceful protest or civic campaigns when our government fails to uphold justice, truth, or its constitutional ideals.

-

We must resist idolatrous nationalism, where the flag replaces the cross, and the nation replaces God.

Such lists are never exhaustive. Every generation must learn to recognize the unique cultural idolatries of its time. One of the rallying cries of the Reformation was semper reformanda—“always reforming.” The Reformers understood that every era presents new challenges that the gospel must confront, not by changing its substance, but by faithfully applying it to new contexts. Only by doing so can the church remain pure, and the mission of the gospel continue to advance.

The Posture We Embody

Perhaps one of the most overlooked aspects of our faith and its transmission is the posture we take in our public life and in our cultural engagement. While sarcasm is a definite and useful tool (1 Kings 18:27; 22:13-28; Job 38:4; Isaiah 44:16-17; Matthew 23:24; 1 Corinthians 4:8; 2 Corinthians 11:19-20), it is not the only tool at our disposal, nor is it proper to use at all times.

As Christians, our posture must be marked by genuine humility, gentleness, and boldness, but ultimately done with love and respect.

I have been in environments where Christians have not been humble or gentle. They have instead employed a posture of antagonism, anger, hostility, and arrogance. Rather than listening and promoting dialogue, or being willing to suffer, they go tit-for-tat. It’s not that Christians don’t try to make their voice heard, vote, or stand up for what’s right. It’s as much how we do it as what we are doing.

The Power We Are Willing (or Unwilling) to Wield

As we examined earlier, Christianity has expanded in one of two ways—the crusader mode or the missionary mode, and the key difference between the two is in how it reacts and wields power. The missionary mode does not have cultural power; therefore, it has to entreat and demonstrate, but it cannot compel. Not so the crusader mode. It will demonstrate and entreat, but when push comes to shove, it will compel.

The missionary mode is the biblical mode of Christian expansion, while the crusader mode leads to great distortion and abuse, something that is antithetical to the gospel.

The missionary mode requires loving, listening, serving, sacrificing, suffering, and, if necessary, dying. We represent a different kingdom, one that does not allow compulsion through worldly power, but displays heavenly power through its countercultural witness.

The Pain We Are Willing to Endure

That’s the key question we have to ask ourselves—are we willing to suffer? In our culture that suffering can be seen on many fronts—relationally, occupationally, and financially. Are we prepared to suffer rather than compromise the gospel?

This is where we can learn from the majority world church, or churches within pluralistic environments. They have much to teach us—helping us to recapture a biblical view of suffering, something that we in the West have largely lost.

We are so used to being the big kids on the cultural block that we have lost our understanding of cruciform suffering to really move the church forward.

The church in the West is declining, but it is not for a want of resources; it is because of a want of comfort and an unwillingness to sacrifice, serve, and suffer for the cause of Christ in our native culture. We can discern and see the purpose of suffering in other cultures, but in our own? That’s much more difficult to grasp and deal with the social implications of.

Guarding Against the Gospel’s Misuse

Martin Luther once said that the Word of God is like a fire—he was simply letting it out. I feel much the same way about the gospel in today’s cultural climate. We have tamed it, twisted it, and used it to serve other ends—whether political ideologies, culture wars, or even well-meaning movements like Alcoholics Anonymous. Christianity, even when stripped of its core, may still offer some societal benefits. But when its essence is removed, it becomes something altogether different—reduced, redefined, and far less than what Christ intended.

As Christians, we must resist all forms of syncretism, but just as urgently, we must resist instrumentalism—using the gospel as a means to an end, even if that end appears noble or socially beneficial. That’s why we must not weaponize it for political gain or co-opt it for culture war victories. To do so is to betray its very nature.

Conclusion:

We are not called to make the gospel serve our agendas, but to be wholly shaped by it. The cross is not a banner we wave in triumph over others, but the place where love absorbed evil and overcame it. If we are to walk in the footsteps of Christ, we must be willing to lose power, reputation, and even comfort for His sake, trusting that resurrection follows crucifixion.

The hope of the world is not found in reclaiming political dominance or winning cultural battles. It is found in the church being the church—a faithful, suffering, Spirit-empowered community that bears witness to the Kingdom of God. That’s how the gospel spreads—not through coercion, but through costly love. That is our call. That is our power. That is our fire.

As the apostle Paul reminds us in 2 Corinthians 4:8-10,

“We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed… always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies.”

John Stoehr, “Russell Moore Claims There Is a Crisis in America—But White Evangelicalism Is Exactly Where It Wants to Be,” Religion Dispatches, August 15, 2023, https://religiondispatches.org/russell-moore-claims-theres-a-crisis-in-evangelical-america-but-white-evangelicalism-is-exactly-where-it-wants-to-be, accessed June 28, 2025.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: HarperOne, 2001), Book 3, Chapter 11.