Over the past few weeks, I’ve been asked for my thoughts on Charlie Kirk and his memorial. Here are some reflections—affirming his faith while offering a critique of certain theological and cultural approaches.

A Shocking Loss

Kirk’s assassination was a horrific tragedy. Beyond the political narratives, there is the deeper loss: a husband, father, and man whose public life shaped conversations on faith and culture. This reflection is not about the motives behind his death, but about understanding Kirk, the messages he championed, and what his life offers for Christians navigating a turbulent cultural climate.

Before I continue, a disclaimer: you may not agree with everything I say because Kirk does not fit neatly into familiar categories.

Setting the Gospel Anchor

Before discussing the memorial and the messages surrounding it, it’s helpful to clarify what I mean by gospel in this article.

The gospel is the good news that the Triune God, in the person of His Son Jesus Christ—fully God and fully man—has fulfilled God’s covenant promises to Israel and all creation through His life, death, and resurrection. Through His ascension and reign, Jesus inaugurates God’s kingdom, offering forgiveness of sins, reconciliation with God, and new life to all who turn from sin and trust in Him by the power of the Holy Spirit.

This salvation is both personal and communal: it restores individuals while initiating the renewal of communities, culture, and creation. God’s people are sent into the world as a new creation community, participating in this restoration by living faithfully in their vocations, relationships, and spheres of influence—proclaiming and embodying God’s truth , promoting justice, and fostering human flourishing.

This mission is carried out without coercion, manipulation, or instrumentalization; it witnesses to the kingdom of God through verbal proclamation, faithful presence, holy living, cruciform suffering, and action. The gospel points forward to the full consummation of God’s reign, when every dimension of creation will reflect His glory and God’s kingdom will be fully realized.

With this foundation, we can move ahead to examine Kirk’s beliefs, thoughts, and approach to cultural engagement.

Affirmation

Though I did not know him personally, I admired much about Kirk. He was a courageous and thoughtful communicator, capable of debating college students with intelligence and respect, and offering hope to people even amid mockery. For a person of faith, it was encouraging to see someone in the public square bravely stand up to ideological streams of thought that opposed the gospel, and to do so with intellectual vigor in often hostile environments.

His organization, Turning Point USA, has remained scandal-free under his leadership, and his family—especially his widow Erika, who publicly forgave his killer—embodies the grace few of us could emulate.

Yet, it was Kirk’s bold affirmation of his faith, love for America, and provocative rhetoric that made him a controversial figure. In many ways, I shared his convictions—the deity of Christ, the reality of sin, the love of the Bible, the importance of family and vocation, the need for moral integrity in public life, the fight for the unborn, critiques of the LGBTQ+ movement, a love of country, and a desire to engage the culture. Yet I also disagreed with key aspects of his approach, particularly his approach to hermeneutics, which heavily influenced how his faith intersected with nationalism and political activism.

Cultural Apologetics as a Lens

To evaluate Kirk’s life, I approach it through cultural apologetics, a framework for analyzing how Christianity interacts with culture to show the reality of the gospel in ways that are both true and satisfying.

Cultural apologetics operates on multiple levels, and one important aspect of its work involves:

-

Analyzing the deep structures of both church culture and broader society.

-

Understanding how these structures affect the viability, authenticity, and communicability of the gospel, both explicitly and implicitly.

-

Redeploying the church to remain faithful to its mission while engaging the cultural realities it inhabits.

Culture is like an iceberg: much lies hidden beneath the surface. Every culture has multiple layers that shape what is considered right, desirable, or normal. These deep structures are often invisible, revealed only when significant events occur, or when someone challenges the assumptions that underlie everyday life—Kirk was one of those challengers.

Cultural apologetics is particularly helpful because it allows us to assess not only what is explicitly communicated but also the implicit messages that shape culture in ways that may subvert or reinforce the gospel.

Explicit & Implicit Messages at the Memorial

Consider the coverage of Kirk’s memorial. Many friends mentioned how encouraging it was to hear the gospel proclaimed. What they appreciated, and what they meant, was that the message of Christ’s atoning death and the offer of salvation was spoken explicitly. Alongside this clear presentation, Kirk’s personal virtues were celebrated—his vision, activism, and work with Turning Point USA were highlighted as markers of a life devoted to purpose and influence.

Yet beneath the explicit affirmations at the memorial, the implicit messages told a more complicated story—framing the gospel, its transmission, and Kirk’s life in ways that demand closer attention.

Christian Nationalism As Gospel Instrumentalization

Kirk sometimes identified as a Christian nationalist, while at other times he avoided the label. Influenced by figures like Lance Wallnau and the New Apostolic Reformation, Kirk often framed loving Christ and loving one’s nation as inseparable, suggesting that Christians bear a responsibility to reclaim America for God.

This perspective treats the gospel as a means to political ends—misusing its power rather than submitting it to its true purpose: the glory of God, the redemption of humanity, and the restoration of creation. While believers are called to seek the good of their communities and nations, the gospel’s central work is salvation, which also inaugurates the renewal of creation.

Bringing all things under Christ’s lordship does not mean coercing or imposing structures by law or political force. Rather, it is realized as God’s people faithfully live in their vocations and communities—embodying truth, promoting justice, and fostering human flourishing—bearing witness to God’s kingdom through presence, action, and cruciform suffering, not political manipulation.

Christians are called to participate in the political sphere, but Christian nationalism places undue emphasis on politics as if it could accomplish what only the church can achieve through its public life. As Michael Wear notes, many in our modern world treat their religion politically and their politics religiously. James Davison Hunter observes that this tendency has arisen, in part, because many Christians have felt shut out of other spheres of influence, leaving only the political arena as a means to act.

I am not saying Christians should avoid politics or fail to use their influence to protect life and promote justice. Using power morally to save lives is necessary. But the church’s primary work—proclaiming the gospel, making disciples, and transforming hearts and communities—is fulfilled through faithful witness, service, and love. Like Jesus, who refused Rome’s coercive power yet accomplished His mission through obedience and love, the church achieves its purpose not through political might but through faithful, God-ordained action. We must resist any rhetoric that treats political power or cultural influence as a substitute for the church’s true calling or that seeks to avoid the path of suffering. Sometimes, as with Joseph, God’s purposes require patience, even imprisonment, for the real mission to be accomplished.

Enemy Mode Framing

Opponents were often framed as existential threats—a posture directly at odds with Jesus’ command to love our enemies—and Republican engagement was equated with Christian fidelity, as if political alignment could substitute for genuine faith. While such framing may feel politically expedient, it undermines the gospel by fostering tribalism, dehumanization, and resistance to dialogue, locking believers into an “enemy mode” mentality. Research shows that in enemy mode it is impossible to love others, yet this is precisely what Jesus calls us to do (Matthew 5:43-44).1,2 True spiritual maturity, therefore, calls us beyond enemy mode—into the difficult but vital work of loving, proclaiming, reasoning, enduring opposition, and even suffering well.

Here we run into a larger imbalance in American Christianity. Our theology of freedom—with its emphasis on liberty, rights, and national identity—is far more developed than our theology of suffering, which the New Testament presents as central to gospel witness (Luke 9:23-24, Acts 14:22, 2 Timothy 2:3-4, et. al). Both are needed to understand and engage the world. A theology of freedom without cruciform suffering (rooted in love for God and love for others) leads to entitlement and even violence. A theology of suffering without freedom risks sanctifying perpetual abuse or passivity.

Held together, they give us a balanced vision: freedom that affirms human dignity and vocation, and suffering that shapes us into a cross-bearing people who embody the way of Jesus. Without that balance, enemy-mode thinking takes hold, the gospel becomes overshadowed by political tribalism, and the message is distorted by the means used to promote it.

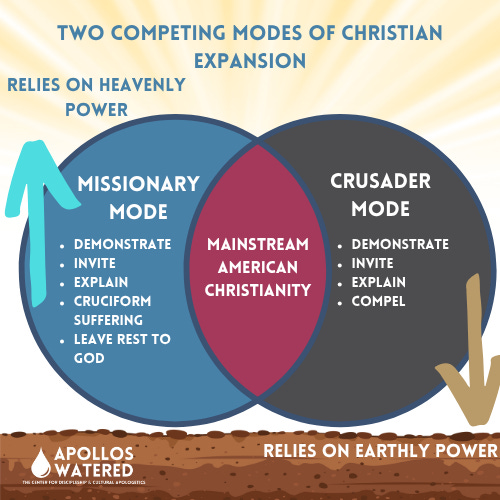

Missionary Mode Vs. Crusader Mode

To understand why these implicit messages are particularly concerning, it is helpful to view them through the historical lens of how Christianity has been transmitted—either in missionary mode or crusader mode. Both modes share similar texts, moral aims, and categories of thought, but they differ fundamentally in their relationship to power.

Missionary mode advances the gospel not by force but through faithful witness, persuasion, humble service, and even cruciform suffering—relying on authenticity and the transformative power of Christ’s love.

Crusader mode, by contrast, seeks to compel belief through coercion, force, or political leverage. Contemporary Christian nationalism exemplifies crusader mode and is deeply problematic for the gospel because it misplaces the focus. Rather than embodying Christ’s self-giving love and the upside-down, cruciform nature of the kingdom, it attempts to achieve the gospel’s ends through legislation, cultural dominance, or coercive authority—means fundamentally at odds with the way God calls the church to bear witness.

Viewed through this lens, the implicit messages at Kirk’s memorial—political polarization, Christian nationalism, and enemy framing—reflect the coercive tendencies of crusader mode. This helps explain why such messaging is not merely a matter of style or rhetoric, but a serious distortion of the gospel’s purpose. While the gospel inaugurates the renewal of creation and calls us to faithful engagement, it does so through presence, persuasion, cruciform suffering, and service—not coercion or the conflation of spiritual and political loyalty.

Distortion occurs when the means of communicating the gospel contradict or undermine its nature. In missionary mode, message and method align: the gospel is proclaimed and embodied through love, service, sacrifice, humility, suffering, and faithful witness, reflecting Christ’s character both explicitly and implicitly.

In crusader mode, by contrast, even correct words can be undermined by coercive, manipulative, or power-driven methods. The result is a gross misrepresentation of the gospel: it becomes associated with domination, political leverage, or social control rather than reconciliation, grace, and the upside-down kingdom of God. Distortion can be explicit, when the content of teaching directly contradicts Christ’s example, or implicit, when the methods used—how the gospel is communicated and embodied—convey values that conflict with the character and kingdom of God.

Beyond misrepresentation, distortion has real relational consequences—it keeps people from seeing and knowing the glorious love of Christ. As Jesus warns against causing “one of these little ones” to stumble (Matthew 18:6) and demonstrates by overturning the temple tables to protect the integrity of prayer and worship (Matthew 21:12-13), anything that hinders genuine relationship, encounter with God, or heartfelt worship distorts the gospel and damages souls. This is why faithful engagement in public life must consider not only what we say, but also how we say it: the method and the message are inseparable, and both must reflect Christ’s love and kingdom in word and deed.

Believers are called to seek the good of their communities and nations, but the gospel’s primary work remains redemptive: bringing salvation, reconciliation, and the renewal of creation—without being reduced to a political tool. In missionary mode, God’s lordship is realized as His people faithfully live in their vocations and communities—embodying truth, promoting justice, and fostering human flourishing—bearing witness to the kingdom through presence, service, cruciform suffering, and action, rather than through coercion, legislation, or political manipulation.

Key Critiques

There are several areas of Kirk’s thought that I believe to be problematic, but I have narrowed them to five main areas that I believe impact all others.

Hermeneutics & Scripture

Kirk often applied Old Testament passages about Israel’s theocracy directly to America, disregarding their historical and theological context. This approach produces confusion and blends the gospel with nationalist impulses.

In one debate, he used Jeremiah 29:7 to defend his view of Christian nationalism, seeing it as a government “ordered by God.”

“But seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.”

But in quoting it, Kirk substituted “seek” for “demanding,” which obviously changes the tone of the passage. By demanding the welfare of the city, he obscures the posture the Israelites were to have. He missed that the social posture of the people in the passage was one of exile—marginalized, powerless, and placed there by God. It was in this status that God was going to use the exiles for his purposes.3 But, Kirk’s use of “demanding” implies cutlural power to bring it about.

One of the more obvious and startling misuses of Scripture comes from the same debate where he quotes the first part of Matthew 16:18,

“Upon this rock I will build my…”

He then pointed to the young man across from him to finish the verse, “Church,” was the response. Kirk restorted:

Kirk’s interpretation is not supported by any mainstream biblical scholarship published in peer-reviewed venues. It is essentially a political re-reading of Scripture, rather than a position grounded in careful study of the Greek text or the historical usage of terms in early Christianity.4

Kirk’s reading is therefore both incorrect and dangerous, reflecting an interpretive lens that conflates the church with political authority. It also serves as a reminder to teachers to exercise caution in instruction (James 3:1).

Immigration & Identity

Kirk often viewed immigration—particularly from non-Western nations—as a potential challenge to America’s Judeo-Christian identity. While there are genuine challenges associated with immigration, a broader concern for the church is the internal secularization of American culture: consumerism, nationalism, materialism, digital narcissism, tribalism, and expressive individualism. These forces can distract the church, weaken communal life, and distort priorities, making it more difficult for faithful gospel witness.

Immigration brings new life to churches and communities, opening opportunities for gospel witness in unexpected ways. God desires to reach all nations (Matthew 28:19-20), and where we have failed to go, He may bring the nations to us or use those who already believe to strengthen His witness. Diverse immigrant communities expose the limits of a gospel too tightly bound to national or cultural identity, reminding the church that the kingdom of God transcends familiar patterns and calls for a faithful, pointed witness to all people.

Church & State

True morality and social cohesion don’t begin in government—they begin in the church. Every citizen brings a moral framework that shapes how they understand justice, freedom, and the common good. Christianity, in particular, offers a vision of human flourishing that goes far beyond laws and policies.

Some, like Charlie Kirk, have argued that church and state should work hand in hand, blurring the lines between the two. But each has a distinct calling.

The church shapes hearts, consciences, and communities that embody justice, mercy, and truth—not through force, not through politics. Government, by contrast, protects rights, maintains order, and enforces justice—but it cannot cultivate virtue. It depends on the character of its citizens, expressed through faithful participation in public life.

When the church steps back—through retreat, assimilation, or silence—it loses its prophetic voice. Society then often turns to laws and political power to define morality. The failures we see in culture are not merely the result of secularization; they reflect the church’s missed opportunity to live and show gospel realities to a watching world.

In such moments, the church is called to a cruciform witness—living faithfully under tension. It offers a compelling model of moral life without coercion, showing that true virtue cannot be legislated without risking oppression. The gospel grants freedom, even when its citizens choose values contrary to it, and in doing so, makes its witness unmistakably attractive.

Lesslie Newbigin saw the church as a symbol and foretaste of God’s kingdom. Its worship, community, and witness point beyond themselves to the reconciled, new creation society God intends. Its authority is formative, not coercive. Christian nationalism, by contrast, collapses this symbolic role into politics, treating the nation as the primary instrument of moral formation.

Sphere sovereignty and subsidiarity highlight the wisdom of distinct roles: family, church, and government each operate best at the level closest to the people involved. When the church abdicates its formative role, society loses both moral guidance and a visible foretaste of God’s kingdom, leaving a vacuum the state cannot rightly fill—and increasing the risk of coercion, corruption, and moral drift.

Biblical vs. Cultural Christianity

This tension becomes clearer when we distinguish biblical Christianity from cultural Christianity. Many Christian nationalists mourn the erosion of “America’s Judeo-Christian heritage,” yet much of what they grieve was merely cultural Christianity—faith in form rather than in substance.5 True Christianity cannot be measured by political dominance or nostalgic ideals. What is needed is not cultural Christianity imposed politically, but biblical Christianity lived publicly—a faith expressed through personal integrity, robust community life, and faithful engagement with society—acting as salt and light, challenging idolatries wherever they appear, without compromising character or conscience.

Civil Rights & Race

Kirk’s rhetoric on race and civil rights was often met with controversy, as biblical scholar Nijay Gupta has noted,

I came across some of his thoughts on race and immigration and MY GOODNESS. Please, read it for yourselves. Just because someone says some things you like doesn’t excuse the things they say or write that are destructively hostile and fundamentally anti-Christian. Like calling for the death of government leaders.

Kirk commented on public-facing civil servant black women like Michelle Obama and Ketanji Brown Jackson, “[these black women] do not have brain processing power to be taken seriously. You have to go steal a white person’s slot.” (JD Vance has contested this, so I encourage you to view the clip of Kirk saying it if you question it as well; I viewed it more than once.) If my pastor said this from the pulpit, I would walk out and I would call for their immediate firing. Wouldn’t you?6

It’s difficult to determine whether Kirk’s inflammatory rhetoric aimed to provoke dialogue or express his true beliefs. While he endorsed equality under the law, his public messaging frequently overshadowed the gospel’s deeper call to reconciliation. It’s no wonder that many black Christian leaders have called him into question.7

Charlie Kirk As A Cultural Symbol

David Fitch has written about Charlie Kirk as a cultural symbol, and after observing my social media feed following his assassination, I am inclined to agree. Fitch places him as the most influential Christian for Gen-Z, and that might be so, but I am more inclined to see his influence through the outrage I saw after his assassination from many of my peers.

I work with Christians from many backgrounds, and it was my white, conservative friends who expressed the most outrage, while my Black, Asian, and Latino/a conservative Christian friends were largely silent. Why? Partly because of Kirk’s statements on race. That explains the silence, but it does not explain the response. Could it be that many of my white friends saw themselves in him—not necessarily sharing all of his ideology, but recognizing someone who boldly articulated and defended what they themselves felt: alienated, left behind, and disoriented in a culture that seemed to have moved on without them.

In Kirk, they perceived a champion of an identity they feel is under threat. Criticism of him felt like criticism of them and their sense of self—that’s why so many in my feed framed it in terms of holy war, revival, and even, in one well-known pastor’s words, a kickoff to the end times.

Pastorally, however, this symbolism can only go so far. While it may spark tribal zeal and some forms of revivalism, it lacks the gospel fuel and clarity necessary for long-term endurance in spiritual formation, gospel-centered witness, and for transmitting the faith beyond tribal boundaries. And left unchecked, it can inflame tribalism and further entrench the culture wars, isolating Christians from those they are called to bless and be blessed by. The real opportunity lies in redirecting this longing toward Christ, transforming a desire for cultural restoration into a hope for gospel clarity, lasting community, and redemptive engagement with the world.

Conclusion: Grief, Critique, Hope

Conclusion: Grief, Critique, Hope

Charlie Kirk’s assassination is a tragedy—for his family, his friends, and for public discourse. I mourn his death and honor his faith, courage, and public witness. He brought difficult conversations into the open and inspired millions—and for that, I am deeply grateful.

At the same time, I must critique the theological missteps of his vision, including the instrumentalization of faith for nationalistic aims, problematic comments on race, and weak hermeneutics. My hope and prayer is that those inspired by his rhetoric in these areas will also be inspired to see beyond it and engage the gospel in a way that is faithful, thoughtful, and life-giving.

Cultural apologetics reminds us that Christianity must remain both true and redemptive: not a tool for political or cultural control, but the power of God to shape hearts, communities, and culture through faithful presence and witness. Honoring Kirk’s memory means learning from both his successes and his mistakes, calling the church to deeper fidelity, and committing ourselves to gospel-centered engagement in the cultural climate we now inhabit.

Jim Wilder & Ray Woolridge, Escaping Enemy Mode: How Our Brains Unite Or Divide Us, Moody Publishers, 2022.

Travis Michael Fleming, Ministry Deep Dive Podcast, #108 | God on Your Brain, Pt. 2 | Jim Wilder, June 17, 2022.

David Fitch, Charlie Kirk Is A Cultural Symbol of the missing church in America, Fitch’s Provocations, September 24, 2025.

In the New Testament, the term ekklesia (ἐκκλησία) refers to a gathering or assembly, typically with a religious meaning, and is used to describe the Christian community. While the term had secular uses in ancient Greece, in the New Testament, it is contextually tied to the formation of a religious community centered on the teachings of Jesus.

James Davison Hunter identifies the root of social thought as a Hybrid Enlightenment, drawing on multiple intellectual currents—most notably Christianity and Enlightenment philosophy, though it was not exclusively one or the other (James Davison Hunter, Democracy and Solidarity, pp. 13–18). Hunter also discussed these ideas in detail as a guest on the Ministry Deep Dive Podcast: episode #246: Building Unity Amid Polarization: Calling You Deeper Than Media Headlines with James Davison Hunter, Pt 1, March 11, 2025; Travis Michael Fleming, Ministry Deep Dive Podcast, episode #247: Building Unity Amid Polarization: Calling You Deeper Than Media Headlines with James Davison Hunter, Pt 2, March 18, 2025.

Nijah Gupta, If You Are Elevating Charlie Kirk, Considering Who You Are Crushing Underfoot, September 19, 2025.

Haleluya Hadero, “Black Clergy and Christians Grapple with Charlie Kirk’s Legacy,” CT Magazine, September 26, 2025.