These days racial issues feel as if they are always front and center. In some ways this is decidedly good news, in others it can be beyond wearying. George Yancey captures the current sentiment when he says

Many of us are tired of fighting the same racial battles over and over again. We are tired of waiting for the next racial controversy to generate more animosity and hostility. We are tired of running into old ideologies that do not serve us well. We are tired of hearing the same arguments and getting nothing done. (p.3)

Two opposing forces—colorblindness and antiracism—currently dominate conversations about race in the US. Yancey works to give proponents of both sides the benefit of the doubt—these are people who actually want things to get better. The problem is, in both cases, important realities are overlooked, people are marginalized, and real progress becomes impossible. In short, both forces fail

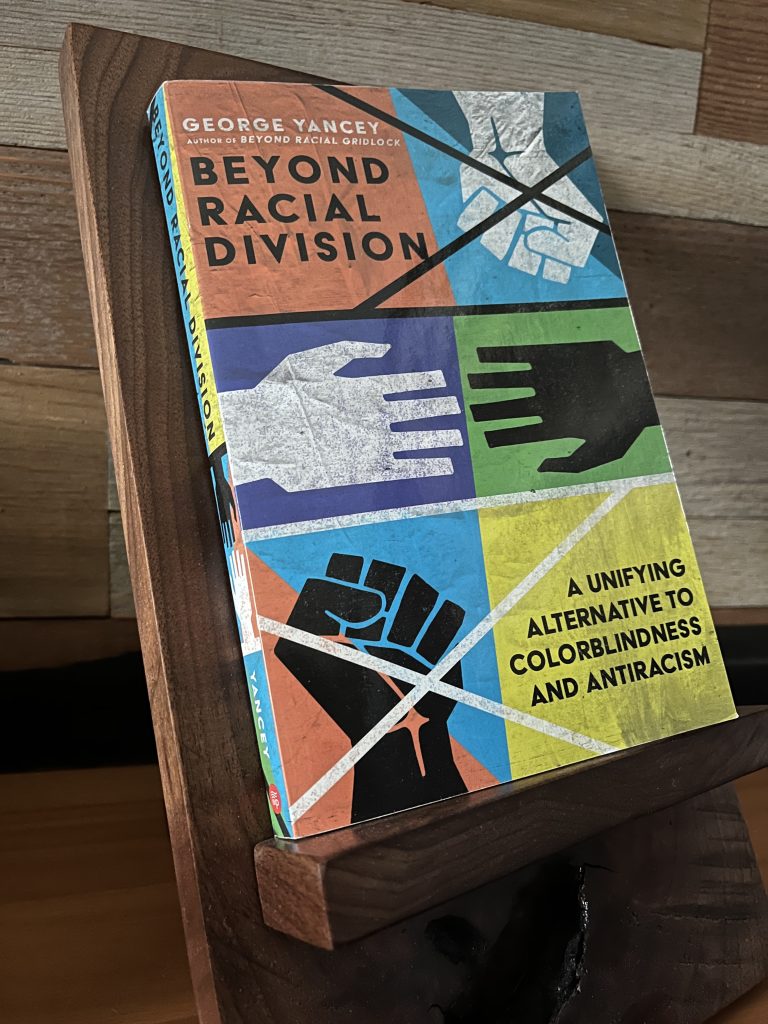

Yancey’s book Beyond Racial Division is an attempt to change the conversation, to set the stage so that we can get something done. This is an important book—a good book that could have been a great book. I admit, I am conflicted about it. The subject is extremely important to both our current cultural moment and to the Church. I believe that Yancey’s overall vision and proposal are spot on. Yet there are a few aspects of the book that give me pause, that make me afraid that Yancey’s proposal will be ignored or dismissed by many. That would be a shame.

Yancey is an African American sociologist specializing in race and ethnicity and religion at Baylor University’s Institute for the Studies of Religion. Married to a Caucasian woman and the father of three sons, Yancey is no spectator to the difficult waters of racial alienation, he lives it daily and wants to help create a better society for everyone and even though he is tired, he remains hopeful that change can be made if all of us stop talking past one another and instead talk to one another.

Yancey asks “How can I break out of my racialized bubble to put forth answers that reflect more than the reality that I am a black man? How can any of us truly free ourselves from the racialized glue sticking us to our own self-defenses and desires for “our people” to be free and to care for all in our society? Recognizing our own weaknesses and biases is a vital first step in dealing with the racial conundrum facing us.” (p. 10)

Yancey’s solution recognizes the very real complexities of the racial alienation which is a part of the American experience. He is neither naïve nor bitter. Instead, Yancey offers what I believe to be a very important solution, a solution that offers real and tangible possibilities for change: Mutual Accountability, or Collaborative Conversations, Yancey does not claim that his approach will be easy or quick, nor does he claim that every last person will be happy. Rather, his approach recognizes that dealing with serious issues like racial tension needs time and effort, it requires moral persuasion by the parties involved, not demanded compliance. At its most basic level, it requires that we actively listen to one another so that we can truly see one another as real human beings, understand each other, and then come to solutions that will benefit everyone. This requires recognizing that we all tend to believe our solutions will benefit everyone when that may not be true. We need to listen to those we are different from, not just to have information, but to truly understand why they believe or feel the way we do. Only when we can put their position in our own words in a way that they would agree with, have we understood them.

If we don’t recognize that one’s race or ethnicity is a deep and integral part of their identity, then we aren’t really treating them as whole people; if we don’t recognize that removing racist laws doesn’t always deal with the effects of racism both in broader societal ways as well for specific individuals, we aren’t dealing with the actual problems of actual people today. At the same time, when the antiracist tries to compel change or demands that whites in particular have a role in solutions that at best always defers to people of color, backlash is inevitable.

Yancey proposes 5 steps for problem solving in relation to racial tensions using mutual accountability:

Define the racial problem

Identify what we have in common

Recognize our cultural or racial differences

Create solutions that answer the concerns of the racial outgroup

Find a compromise solution that works best for all.

One of the book’s greatest strengths is Yancey’s regular citation of studies that show how colorblindness and antiracism don’t work in the real world, how even with the best of intentions, these approaches are destined to fail. In chapter 5, Yancey provides evidence from sociology as well as the stories of real people that strongly suggest mutual accountability holds the best hope for lasting solutions. For example, the contact hypothesis has shown that the more interaction we have with groups the less likely we are to be negatively biased toward them. Other studies show that when we share an overarching identity with someone, we start seeing them as a part of “us” instead of “them” and tensions decrease.

To this point in the book I have had questions here and there, would like for Yancey to unpack a few ideas or give better grounding for some of his statements, but have tracked with him in large part. Chapter 6, The Theological Basis for Mutual Accountability, fell short of what I hoped for. As someone for whom theology really matters, I was looking for some specific tools to help show people why this important work matters. How does the Bible address issues surrounding ethnicity and race? Are there theological principles that we can bring to the table that address some of the objections of people either the colorblind or antiracist camps? To those who are skeptical of any direct dealing with this issue? Unfortunately, the chapter left me wanting a lot more.

Yancey follows the scholarly argument that the idea of race developed in reaction to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. To be sure, there is historical evidence to show that there is much truth in this assertion. It falls short, however, of biblical reality. No, the Bible does not follow modern notions of race, it could not. At the same time, the Bible regularly deals with ethnic and racial differences and outgroups. Yancey’s own illustration of the Samaritans shows that ethnic or racial prejudice does exist in Scripture. Looking to the Old Testament interactions of the nations, as well as New Testament passages about the makeup of the church in Acts (e.g., Cornelius and Peter in ch. 10, the leadership at Antioch in ch. 13), as well as Paul’s clear instruction that ethnicity should not be a factor in who is or can be a Christian (Col. 3:11) would give a much more solid grounding for arguing against racist tendencies. It is also arguable that the Babel story in Genesis 11 can help us to understand racial animosities between groups.

Additionally, Yancey argues that the doctrine of depravity sets Christians apart from other philosophies and offers a means to combat racial alienation. While there is no question that the Bible clearly teaches human depravity starting in Genesis 3, and Yancey is not alone in starting here, it is the wrong place from which to start. Genesis 1 says God created all of humanity in his image. That is the appropriate starting place because it demands that all humans acknowledge all other humans as bearing God’s image. God creates well and even the fall cannot totally erase the image of God in humanity—human beings simply are not powerful enough to completely erase God’s image in us. Only when this baseline has been established will discussions of human depravity a) truly show the depth of our issues and b) offer a way forward for solutions to racism. Yancey believes that recognizing human depravity will make us recognize that human rationality alone can’t solve racial problems. While I agree, it is precisely in the fact that we were first created in the image of God that we have any hope of answering this difficult issue. It is because, while broken, the image of God in humanity is not erased we can look to solutions for humanity’s problems—including racism—even with or through non-Christians. I found myself questioning several of the assertions Yancey made about why focusing on human depravity is key. Again, I believe in human depravity, but without the Image of God first, I would be inclined to feel hopeless about our ability to actually solve any of these issues.

Chapter seven moves from foundations to the practical outworking of mutual accountability in our day to day lives: it will take an ongoing commitment; we will need to be humble in our approach and seek out interracial relationships; we will need to recognize our own biases and overcome our fears. All of these are good reminders. In what is arguably the most powerful aspect of the chapter, and perhaps the book, Yancey uses three versions of an analogy of an abusive marriage to help people see the difficulties surrounding racial tensions in America. As powerful as it is, I am afraid that those who need it most will likely reject it, believing that it may have been true in the past but it is not now. Nevertheless, for those willing to listen, it is quite moving and helpful. The final chapter gives illustrations of individuals and organizations who are working to effect change where they are, which is both a helpful and hopeful note on which to end the book.

As I said earlier, I am conflicted. I believe that Yancey is correct. He has shown through research and experience why antiracism and colorblindness are destined to fail and how mutual accountability can be a path forward. But I was left wanting more. In addition to my theological issues, there were quite a few concepts that I felt needed serious unpacking for me to truly understand or accept. Some of these were brought up fairly late in the book. No doubt at least some are simply assumed or understood in his field, but to me, and to average people trying to get a handle on this thorny issue, that was just not the case.

Perhaps my biggest concern is about what wasn’t in the book—answer to the fundamental question “why”. Why should we care? Why should anyone—black, white, Asian, Hispanic—anyone, put in the kind of effort this will take? It is simply assumed that we should want things to be better for everyone (we should!). Unfortunately, all too often, it seems that many, including Christians, just don’t care. Without the crucial belief that all humanity is created in the image of God, I am afraid that for many, there just is not enough motivation to make oneself or one’s community vulnerable and take on the hard work of mutual accountability. I hope I am wrong, because what Yancey is proposing is important. Even though I have serious questions and even some disagreements, I believe he is largely correct.

Get the book. Read it. Listen well. Argue if you must, but take his perspective into account and see what you learn. You will be glad you did (even if it leaves you wanting more).