“Sadly, many Christians default toward a naive embrace of technology as a neutral or merely pragmatic tool to be harnessed for mission. But as Postman—following McLuhan—rightly argued, what we think about, the symbols and metaphors we think with, and the forums in which thoughts develop.” (p. 10)

Technology is never neutral. Every innovation reshapes us, often in ways we fail to notice. Yet few Christians think this way. Too often, we assume that digital tools are simply neutral conduits for gospel proclamation. In theory, that sounds compelling. In practice, it comes with significant costs.

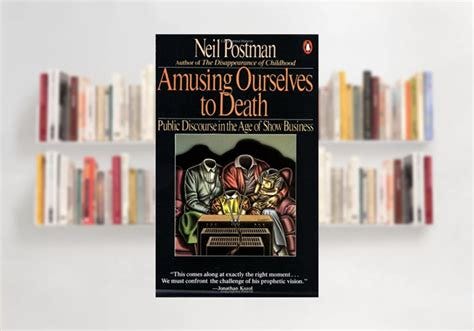

In Scrolling Ourselves to Death, the authors, drawing inspiration from Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death—extend Postman’s critique into the digital age. Postman, who died before the rise of smartphones and social media, foresaw the cultural impact of entertainment-driven media. McCracken and Mesa pick up where he left off, showing how our devices and platforms are not only delivering content but reshaping the very conditions of our discipleship, worship, and witness.

This collection of essays, written by contributors to The Gospel Coalition, offers both cultural analysis and practical wisdom. McCracken, who helped pioneer TGC’s online presence, is an ideal editor for the project. He avoids simplistic rejection of technology; smartphones and digital platforms are here to stay. Instead, the book seeks a discerning, non-idolatrous approach to life in the online world.

The volume is organized into three sections:

-

Revisiting Postman—highlighting his enduring insights and applying them to today’s media landscape.

-

Confronting the Challenges—exploring the practical implications for Christian leaders and communicators.

-

Charting a Way Forward—offering hopeful, realistic practices for resisting digital captivity and reclaiming life in a screen-saturated age.

Strengths

The strength of the book lies in its breadth of authors and its willingness to talk frankly about how technology affects gospel communication. For far too long, ministry leaders have uncritically adopted technological implications without considering how the medium shapes the message itself.1

A second strength is how the authors build on Postman’s prescient insight into media’s psychological and spiritual effects, placing it within an Orwellian and Huxleyan framework. Orwell saw fear as a mechanism to conform, while Huxley saw pleasure. Both approaches still shape culture, but it is the Huxleyan path—pleasure and dopamine-driven media—that dominates today.

“We’re amusing ourselves into addiction. Entertainment culture metastasized into something not even Postman could have predicted: dopamine media. …Your phone is a digital syringe” (p. 20–21).

The authors contends that digital media and technopoly don’t just distract us—they actively deform us.

Key Points

#1. A New Despair Machine

Rather than bringing out the gospel—the good news of Christ’s kingdom, forgiveness, and eternal life—our digital media has become a “despair machine” that seeks to “perpetuate despair in the human soul” (p. 188). It creates the illusion of awareness and action while leaving us paralyzed or numbed. As the church has adopted it uncritically, it has given rise to an entirely new set of problems.

#2. The Church’s New Problems

One of COVID’s many effects was to move services online. After COVID ended, some returned while others chose to stay. While initially a necessity, continuing online services purely for convenience comes at a cost—it turns worship into something to consume. By participating in this practice, low commitment is enabled, and the friction, sacrifice, and embodied demands of true community are removed (p. 193).

In churches that continue to offer internet services, the common justification is, “we are meeting people where they are.” While often rooted in a genuine desire to reach the lost, this approach must be weighed against Jesus’ radical call to full participation in him—“unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (John 6:53). The cost of discipleship is high. Convenience-driven online participation may broaden access but risks hollowing out the embodied, high-commitment practices that shape authentic Christian community.

#3. The Dangers of “Rear-View Mirror Thinking”

Both Postman and his mentor, McLuhan, saw technology as far from neutral. Treating new tech as merely an extension of the old is naïve, particularly for the church. Those who view digital church as an upgrade fail to appreciate the embodied nature of the Christian faith and may inadvertently attack it (p. 193).

The authors note that “insta-evangelists” who see “church as content” commodify Christianity, deforming it into “easy and amusing Christianity” (p. 196).

#4. Embodiment vs. Disembodiment

Embodiment is necessary for real belonging. The authors point to Scripture to show that household belonging (Eph. 2:19) requires presence and relational investment. Online communities offer belonging without cost, and in catering to that, churches have failed to recognize that people crave the difficulty of true commitment. Practices Scripture emphasizes—hospitality, empathy, and embodied presence—cannot be reduced to packaged digital content (pp. 197–200).

#5. Technopoly & the Feedback Loop

Postman describes technopoly as occurring when culture stops merely using tools and begins being shaped by them without noticing (pp. 210–211). For example, the disappearance of payphones and the ubiquity of mobile phones create dependency, reinforcing mass adoption. Technology, by nature, isolates, weakening community and undermining the structures needed to resist its dominance.

Breaking this feedback loop requires “loving resistance fighters” who embody alternative rhythms, creating habits of resistance through spiritual disciplines and individual boundaries. Churches are not immune—they too must cultivate communal habits of spiritual digital formation that foster discernment, media awareness, and counter-formative practices.

#6. The Counter-Vision

One of the greatest strengths the authors offer is the contention that the church can offer what technopoly erodes: embodied, costly, high-commitment, joyful community. Postman, though Jewish, recognized the church’s unique resources to resist the isolating effects of technology. The strategy, then, is not to out-tech the world, but to out-embody it—through presence, belonging, sacrifice, and gospel-rooted practices of resistance.

Weaknesses

While I thoroughly enjoyed the book, a few weaknesses stand out:

#1. More Descriptive, Less Prescriptive

The book effectively diagnoses the problem, but prescriptive guidance is limited. For example:

-

Can digital services help those who are shut-in while still advocating for embodiment?

-

Are there models of churches using technology to raise awareness without reducing commitment?

#2. Western Contextual Bias

The primary examples are Western. How might these lessons apply where embodied presence is dangerous, such as in persecuted churches? Online ministry in China has a much longer history, and majority-world perspectives could strengthen the discussion.

#3. Clarifying Technology’s Role

The book critiques technology but could explore its redeemed use more deeply. How can churches adopt technology wisely without succumbing to its idolatrous or isolating effects? More theological and practical parameters would be helpful.

Final Thoughts

Scrolling Ourselves to Death is an insightful and necessary read for any ministry leader wrestling with the role of technology. For those who have uncritically adopted digital tools, it offers a strong corrective. For those already convinced, it provides additional categories and arguments for resisting digital idolatry. For those seeking positive examples of wise technology use, the book leaves some gaps.

Still, despite minor weaknesses, the book is essential for anyone sensing that technology has gone beyond wisdom—this work can increase discernment and help reduce digital overexposure.

The Apollos Watered Rating: 💧💧💧💧½ (4 ½ drops) Nearly Essential

Scrolling Ourselves to Death: Reclaiming Life In A Digital Age

Edited by Brett McCracken and Ivan Mesa

Crossway, 2025. 256 pages.

💧 The Apollo’s Watered Review Rating System:

💧💧💧💧💧 (5 drops) Must Read:

Foundational, insightful, and transformative for ministry leaders. Everyone in your sphere should read it.

💧💧💧💧½ (4 ½ drops) Nearly Essential:

Excellent and compelling. Just shy of “must read,” but still highly recommended.

💧💧💧💧 (4 drops) Should Read:

Strong contribution. Valuable for most readers in your context.

💧💧💧½ (3 ½ drops) Helpful if Interested:

Worthwhile for those with a specific interest or need.

💧💧💧 (3 drops) Situationally Useful:

Some good insights, but not broadly applicable. It might serve a limited purpose.

💧💧½ or less (2 ½ drops or less) Skim or Leave It Be:

Little lasting value. May have a point or two, but better options are available.

💧½ or 💧 — (1 ½ or 1 drop) Skip It:

Weak or misleading. Not worth your time

McCracken and Mesa note that tech-savvy churches are predominantly evangelical, while Roman Catholics, Orthodox, and mainline Protestants have largely resisted new technologies—something scholars have barely studied. Perhaps the draw of younger generations to Catholicism, Anglicanism, and Orthodoxy lies in precisely this refusal: their capacity to maintain transcendence, rather than try to manufacture it.