“How did we get to place culturally where the statement ‘I am a woman trapped in a man’s body’ is universally understood as both coherent and meaningful?” (19) asks historian and professor of biblical and religious studies Carl Trueman in his recent book The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self. Trueman says that less than 30 years ago his grandfather would have considered the statement “a piece of incoherent gibberish” (19) and sets off on an exploration to understand how got here. It’s an important question for all of us because contemporary culture makes sexual identity the defining marker of our authentic selves. Trueman’s focus on the roots of our understanding of sex and is necessary to understanding our times. But the issue is deeper than we might realize.

We have all made comments like “I don’t feel like myself today,” or “that’s not really me.”

We have all felt some kind of disconnect between who we are on the inside and who we are on the outside. We prioritize our inner life as somehow the most real, the most authentic understanding of who we. Most often we don’t even know we are doing it. Trueman argues:

It is the very essence of the culture of which we are all a part. To put it bluntly: we are all expressive individualists now. Just as some choose to identify themselves by their sexual orientation, so the religious person chooses to be a Christian or a Muslim. And this raises the question of why society finds some choices to be legitimate and others to be irrelevant or unacceptable (25).

Coming in at over 400 pages, the book is neither short nor easy. It traces a pathway through political theorists and poets, mad philosophers, psychologists, scientists, and economic revolutionaries, up to and through the sexual revolution of the mid 20th century. Trueman is a good writer, much easier to read than the often-tortured writing of many academics, but he is swimming in deep waters. This is a very important, if dense work. It is not a book for everyone, and it takes time to adequately process.

In the introduction (29-31), Trueman is quite clear in what he is and is not trying to do in this book. He wants to show that certain ideas from key figures now “permeate our culture at all levels” (29), that we must understand the problems of our time and culture and respond appropriately. It is not an exhaustive account of how these ideas came to permeate our culture, nor a lament, nor a critique as such.

Remembering both what this book is trying to do and what it is not trying to do is important. Some of my biggest frustrations with the book came because I wanted Trueman to do something he was not intending to do—I wanted critique, I wanted to understand the how as much as the that of the history he traces.

The book is broken into four parts, each tracing a part of the story. Part 1, Architecture of the Revolution introduces us to Reiff, Taylor and MacIntyre, whose thought help us understand how cultures have historically understood the world as compared to how we do so today—the contemporary West has completely rewritten how we understand both the self and culture.

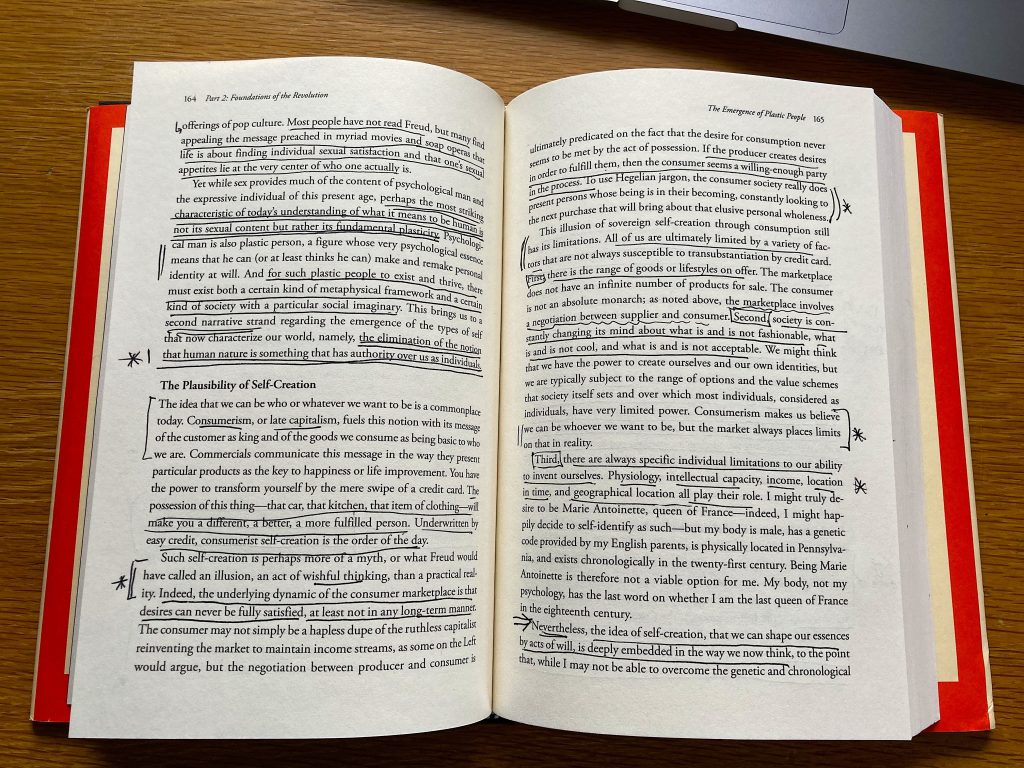

Part 2, Foundations of the Revolution, begins to trace how the story changed so radically. Beginning with Jean Jacques Rousseau, through the Romantic poets Wordsworth, Shelley, and Blake, and on to Nietzsche, Marx, and Darwin, Trueman paints a picture of how the Western understanding of the self gradually moved from being connected to a transcendent and coherent truth to which we must conform, to one where the self is defined but by me: what I feel, and what I want my self to be.

In Part 3, Sexualization of the revolution, Trueman turns to the work of Freud. Where the earlier thinkers and the Romantic poets wanted to break free of the sexual limits of Western civilization, they still saw it as something one did. Freud changed everything, arguing that sex is fundamental to who we are. This new framing intentionally throws off old traditions and religious belief. When Freud’s work is wed to Marxist philosophy, sex becomes decidedly political. From here, we see the heart of the matter:

“[W]hen we start to think about sexual morality today, we need to understand we are actually thinking about what it means to be human. Discussions of what does and does not constitute legitimate sexual behavior cannot be abstracted from that deeper question” (264).

Many Christians today simply do not understand that this is the question we are dealing with and why the stakes are so high for those who oppose traditional Christian teaching on sexuality.

Part 4, Triumphs of the Revolution, moves to the contemporary world of the mid 20th century and today. From pornography to feminism, pop culture to the US Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision, Peter Singer, free speech on college campuses and the surprisingly contradictory coalition that is the LGBTQ+ alliance, Trueman argues that the trajectory established in Parts 1-3 is now working its way out in society. Part 4 ends with this chilling statement:

transgenderism adds a dimension to that reality that goes far beyond that created by lesbianism, homosexuality, and bisexuality. With transgenderism, identity is almost entirely internalized, so that in theory a parent does not necessarily know whether a particular child is a son or daughter. Such thinking not only places huge responsibility on the shoulders of the child . . . , it also places potentially huge power in the hands of the government, of the medical profession, and of the various lobby groups to whose tune they tend to dance” (377-378).

Finally, the concluding Unscientific Prologue, offers a (far too) brief look at both the dangers ahead for the church as well as some things we can do. Christians must be careful not to fall into the same kind of thinking that plagues our wider society—viewing those whose views we oppose simply as oppressors, seeing everything through the lens of a personal narrative isolated from a larger theological framework, or resorting to sarcasm and insult. Instead, we must “think long and hard about the causes, their wider ramifications, and our relationship as Christians to them” (390). This means first understanding that LGBTQ+ debates are not primarily about behavior but identity. Because identity and belonging are fundamental to the human condition, we must recognize and address issues of identity at a foundational level. Trueman is not optimistic and believes that religious freedom, especially for Christians, will be under increasing attack in the days to come.

Trueman ends with three the church should do.

- “the church should reflect long and hard on the connection between aesthetics and her core beliefs and practices” (402, italics Trueman’s). He believes that the church should not indulge in “the aesthetic strategy of the wider culture” (403).

- The church must “be a community” (403). Our human need for belonging is a place where the church can both thrive, and somewhat ironically learn from the LGBTQ+ community—who actually act as a community when too often we do not.

- “Protestants need to recover both natural law and a high view of the physical body” (405). Here Trueman is mostly concerned about our ability to coherently teach moral principles to our own people. “A recovery of a biblical understanding of embodiment is vital. And closely allied with this is the fact that the church must maintain its commitment to biblical sexual morality, whatever the social cost might be” (406).

Almost as an afterthought, Trueman adds a significant point: Christianity is a religion “both rooted in historical events and transmitted through history via the church” (405). This means we can look to the past to find solutions to the present. He points to the second century as both precedent for our time and hope for solutions:

In the second century, the church was a maligned sect within a dominant pluralist society. She was under suspicion . . . because she appeared subversive in claiming Jesus as King and was viewed as immoral . . ..

This is where we are today. . . . a pluralist society [that] has slowly but surely adopted beliefs, particularly beliefs about sexuality and identity, that render Christianity immoral and inimical to the civic stability of society as now understood. . . .

It was the second-century world, of course, that laid down the foundations for the later successes of the third and fourth centuries. And she did it by what means? By existing as a close-knit, doctrinally bounded community that required her members to act consistently with their faith and to be good citizens of the earthly city as far as good citizenship was compatible with faithfulness to Christ (407).

The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self has painted a more than plausible picture of how we got to where we are and I am grateful for his work. But there are things I wish he had done. Some he told us he wasn’t going to. Others, feel missing from an otherwise comprehensive book. Here are my quibbles (and they are—mostly—quibbles):

- For all of the significance of American society and thinking in the promotion of the sexual revolution around the world, there are basically no American voices until the 20th century. While America hasn’t been around that long, it still seems there should be more attention here, especially on the artistic and popular fronts (cinema, music, etc.).

- Several times Trueman refers to the very important role technology plays in the development of the inner psychological self and, more significantly the very possibility of transgenderism (drugs and surgeries making possible what could not have been possible earlier), yet he barely covers this crucial topic. I believe that technology has a far greater impact on our understanding of the self than he addresses.

- For most of the book, Trueman approaches his subjects with a historian’s characteristic detachment. While an accurate reporting is certainly important, it would have been useful to also include a critique of these major figures. The poet Shelley’s own life, for example, seems a perfect means to show that the very ideas he promoted didn’t work—he left a trail of misery and heartache wherever he went.

- There is virtually no discussion of Christian thinking throughout the book. As a history, surely there were Christian thinkers all along this trajectory who could have provided counterpoints. Were Christian thinkers largely captured by the same kinds of movements? Either way the story seems incomplete without exploring Christian thinkers.

- Similarly, what about other streams of thought? Why did these ideas take and not those of other thinkers? I largely agree with Trueman’s picture and conclusions, but it would be nice to know why these ideas won the day.

- How exactly did these ideas became such broad cultural categories? Trueman repeatedly says that most people never read these thinkers but their ideas seep into the culture. The Romantic poets and other artistic movements provide some possibilities, but again, how much do they impact the average person? Most people don’t read poetry today and it is not clear that they did in the 18th century. Instead, they hear bad poetry in the form of pop songs. Most people don’t go to art galleries or care about what is there. They view movies and absorb advertising; they scroll through Instagram. This is where a connection to popular culture as well as the elites is important. Arguably the increase in exposure to the ideas of these thinkers post World War 2 is due to the increase of people going to universities, but what about prior to world War 2?

- I am not entirely sure that I agree with Trueman’s warning not to indulge in the aesthetics of the contemporary culture, but I may be misunderstanding his point. He shows quite clearly that we humans are deeply influenced by aesthetics, It seems to me that one of the reasons that Christian thinking lost so much of the Western social imaginary is precisely because we were not connecting the aesthetic and the rational as well as those who led us down the path to the rise and triumph of the modern self.

- Finally, the church needs more than the historical realities behind where we are (we certainly do need this!). We need a way forward. We need resources to thoughtfully make our way in and through our contemporary context. We need a highly expanded version of Trueman’s final Concluding Unscientific Prologue.

Again, these are more quibbles that deep seated concerns. The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self was a tough but remarkable read. I believe Trueman has provided a resource that will set the stage for more important works to come. I highly recommend that pastors, teachers, and thoughtful Christians take the time to read this important work. Be Sure to listen to Travis’s interview with Carl.

Disclaimer: I received a copy of The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self free from Crossway to review for Apollos Watered’s podcast with Carl Trueman. I was not required to give a positive review, and this review reflects my honest opinion.