This topic will be covered in six parts. This is part 1.

The Disorientation: The Changing Cultural & Political Landscape

On June 14, 2007, I stood at historic Boston Common near the Massachusetts State House, advocating for the right of citizens to vote on a definition of marriage as between one man and one woman. The goal was simple: get the question on the 2008 ballot.

It was tense. Police on horseback lined the streets. Wooden yellow barricades separated demonstrators to prevent violence.

On the State House steps stood the supporters of same-sex marriage—men, women, and even children, holding rainbow posters and singing songs like “We Shall Overcome,” intentionally linking their movement with the civil rights struggles of a generation before.

In comparison, our group was small. A pastor friend joined me. We were given hunter green stickers to wear and handed a long banner, which we both held, while others nearby carried matching placards.

We were passionate but vastly outnumbered—ten to one by some estimates. Beacon Street traffic still flowed, splitting our demonstration. At red lights, drivers often rolled down their windows to cheer the pro–same-sex marriage group and give us the finger, accompanied by harsh expletives.

It didn’t help that some on our side resorted to screaming and name-calling. Their animated bodies, red faces, and flying spittle did more to damage our cause than help it. While I was passionate and deeply concerned about the societal impact of redefining marriage, I didn’t want to be associated with that behavior. What was needed was compassionate resolve. We weren’t demanding a veto—we were simply asking for the chance to vote, as over 123,000 signatories had petitioned.

After about an hour, I felt the need for a break. I signaled to my friend, and we handed off the banner to two eager latecomers. We made our way to the public men’s room in Boston Common.

That’s when things got strange.

Just as we entered, two men wearing rainbow stickers were exiting. Each of us—two from opposite sides of the cultural divide—wore our ideological identity on our chest. The air was thick with silence and tension, mixed with the usual smell of a public restroom. My adrenaline spiked. My heart raced. Were we about to fight?

Outdoors, we were separated by barricades and a busy street. But here, we were face to face.

For a long moment—though really only a few seconds—none of us moved. Then the men exited, and the tension broke. My friend and I both exhaled in relief, coming down from the rush. I am sure that they felt the same.

But as I left the restroom, a deeper emotion began to stir: sorrow.

The same-sex marriage community was present, organized, and singing songs rooted in Scripture.

Where were the Christians?

I looked up to heaven and silently asked, “God, where is Your Church?”

Just then, a loud sound rang out—a drum, a trumpet, a shout? I can’t recall exactly. But it was enough to catch my attention.

I turned, overjoyed, thinking reinforcements had arrived. The cavalry was here. Maybe now our numbers would be balanced!

They held a banner: “Thirty churches united…”

My heart leapt—until I read the rest.

“…for same-sex marriage.”

My heart sank.

I looked at my friend. We both nodded. No words were needed. We had lost.

We walked back to the car in silence and drove home.

Soon after, the results were in. Despite the citizen support and record number of signatures, the legislature voted 151–45 against putting the question on the ballot.

Same-sex marriage became the law of the land in Massachusetts.

I’ve thought often about that day. Some reading this may celebrate what happened. Others will feel the sorrow I felt.

Before you rush to leave an angry comment, please hear me: we are all sinners.

Each of us, without exception, stands guilty before God. Our sins may manifest differently, but the same inherited brokenness marks all of us, but that is an article for another day.

Suffice it to say, we are all in need of redemption.

I share this story because many Christians—like me—have felt increasingly displaced.

Marginalized.

Not out of hatred or fear, but because they feel like collateral damage in a culture that seems to be accelerating away from biblical truth.

You may not share that perspective—and that’s okay.

Disagreement is part of honest dialogue.

You might argue that others have felt disenfranchised far longer, and that’s a valid conversation to have. But for now, I simply ask that you try to understand the emotional and spiritual context in which many Christian nationalists emerge.

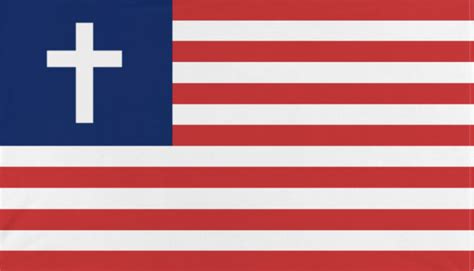

This is the soil—the sorrow, the disorientation, the longing—in which the seeds of Christian nationalism are often sown.

Let me say up front: I am not a Christian nationalist. I don’t identify with that label—for reasons that will soon become clear. But I do understand it, because I believe that it has similar emotional and psychological roots to what I have felt.

My goal in this series is to take a deep dive into Christian nationalism—what it is, what it is not—and to examine its claims biblically, theologically, historically, psychologically, and sociologically.

This isn’t about partisanship. It’s not about lifting up one political ideology over another. It’s about discerning whether the vision of public life offered by Christian nationalism aligns with the heart of God revealed in Scripture.

In the next article, I invite you to come with me—gently, carefully, and prayerfully—as we begin to explore what Christian nationalism really is, starting with how its own proponents define it. Let’s pursue understanding, not outrage. Let’s seek clarity, not caricature. And above all, let’s keep our eyes fixed on Christ.