Why did the church I grew up in close its doors?

Why have 26 Christian colleges and seminaries shut down or merged since COVID?

Why have 40 million people stopped attending church in the last 25 years?

Why are pastors burning out in record numbers?

Why has Christianity declined so rapidly—and more to the point, why has it become culturally obsolete?

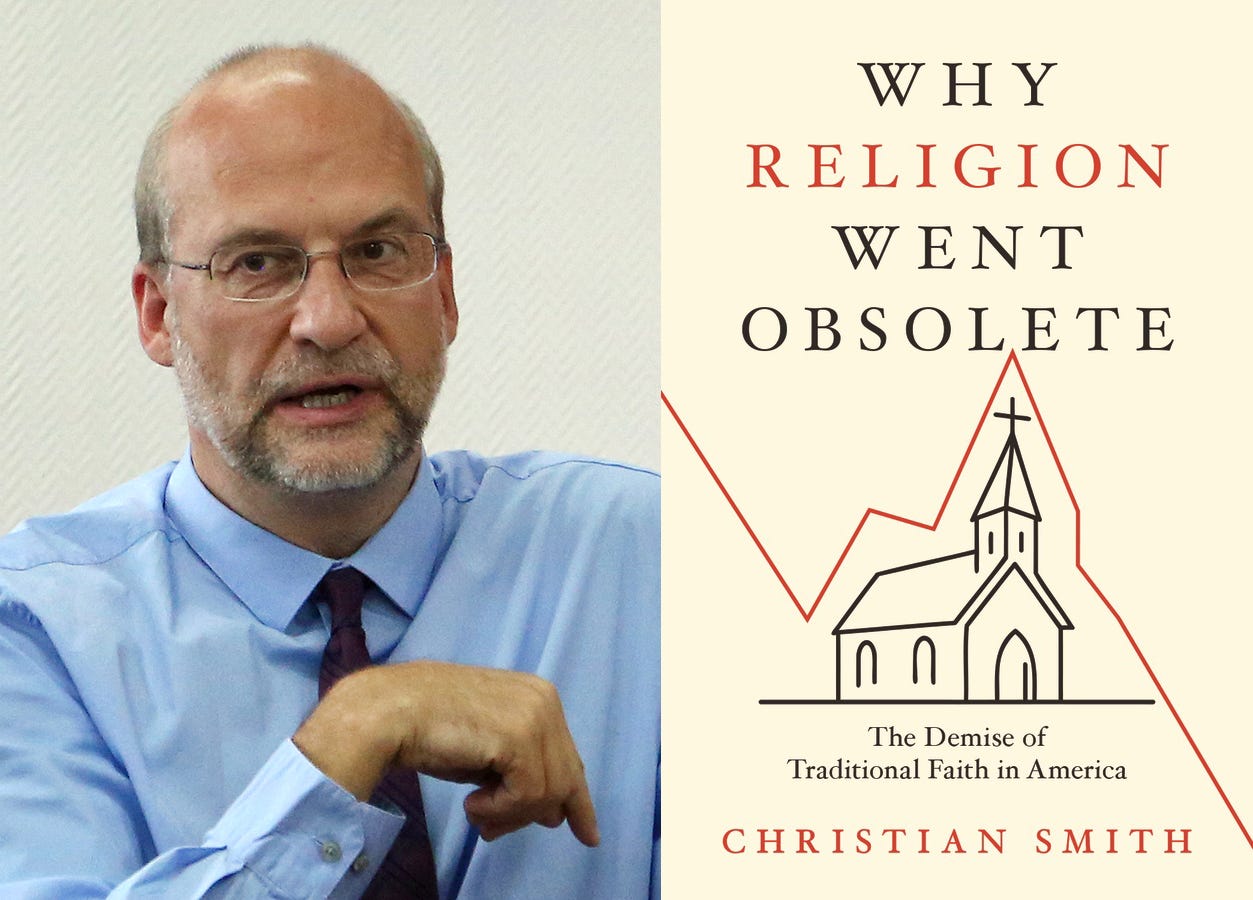

These are the kind of questions that lie at the heart of Christian Smith’s insightful and opportune book, Why Religion Became Obsolete (Oxford University Press, 2025). In it, Smith—one of America’s leading sociologists of religion—does more than present statistics or trends. He offers what might be called a cultural MRI: a deep diagnostic look into the spiritual condition of American society and why traditional Christianity no longer makes sense to so many.

The Cultural Obsolescence of Traditional Religion

Smith’s central claim is unsurprising but wonderfully illuminating: American traditional religion—faith expressions deeply rooted in communities across multiple generations—hasn’t merely declined; it has become culturally obsolete (p. 2). This obsolescence, he argues, is not the result of a single event or ideology but a convergence of cultural, philosophical, institutional, and emotional shifts. This perfect ideological storm has slowly eroded the foundations of traditional faith in America.

Rather than lay blame at the usual suspects of cultural tropes—secularism, politics, media, or the sexual revolution—Smith digs deeper, bringing much-needed clarity to how culture actually functions. He explores how modern Americans construct meaning, see authority, form identity, and view institutions. His thesis isn’t that people stopped believing in God, but that belief itself in the traditional institutional forms has become implausible. In today’s cultural atmosphere, traditional religious faith no longer feels viable.

Defining the Landscape

Smith begins by defining his terms and outlining the structure of his argument (section 1). He is less concerned with numerical decline and more with cultural ethos—the invisible atmosphere that is suffocating American traditional religion. He doesn’t dismiss religion entirely but posits a certain cultural form of belief that has endured. Building on his earlier work on Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, he shows how this thin, privatized spirituality now dominates the American religious imagination.

He introduces a series of memorable metaphors to frame the issue: “cultural mismatch” (p. 62), “particulate matter in the atmosphere” (p. 64), and “crowding out” (p. 68), helping readers visualize the slow, subtle forces that have displaced traditional religion.

Mapping the Cultural Decline

With his framework in place, Smith spends the next section of the book tracing the major social and cultural trends from the 1990s through the 2000s. He particularly zeroes in on Millennials, showing how this generation has been uniquely shaped by events and values that make traditional Christianity feel foreign—or worse, oppressive. The final section examines key cultural figures and movements that helped embed these new sensibilities into public consciousness. These chapters are rich—if at times uneven—but still wonderfully illuminating.

Televangelism, Scandals, and the Culture Wars

While Smith emphasizes external sociocultural forces, he does not excuse the American church from its role in its marginalization.

The rise of televangelism—with its blend of spectacle, emotionalism, and consumer appeal—transformed worship into performance and pastors into celebrities. What began as innovative outreach devolved into a branding machine, often masking shallow theology and setting the stage for public failure. The prosperity gospel didn’t merely distort Christian teaching—it damaged the Church’s moral credibility.

Then came the scandals—financial, sexual, and institutional. From Catholic dioceses to megachurch platforms, these failures didn’t just provoke outrage—they confirmed deep cultural suspicions: that Christianity is hypocritical, power-hungry, and unsafe. In a society already skeptical of authority and institutions, such collapses did immeasurable harm.

Add to this the culture wars, where Christian witness was too often conflated with partisan combat. Instead of being known for grace, humility, and justice, much of the church became identified with anger, preoccupied by nostalgia, and grasping for control. In trying to “win” the culture, we often lost its respect. These self-inflicted wounds helped accelerate the very obsolescence Smith describes.

Although Smith doesn’t dwell heavily on these internal failures, they cast a long shadow over the rest of his argument. In the court of public opinion, Christianity hasn’t just become unbelievable—it has become untrustworthy. One can’t help but recall Aaron Renn’s observation that we’ve entered the Negative World.

In many ways, Smith’s work provides a rationale for the existence of Apollos Watered and the urgent need for cultural apologetics. In many respects, Why Religion Went Obsolete is a manifesto for the need for cultural apologetics. Christianity must go beyond traditional argumentation to embody integrity, repentance, and relational credibility. Our task is not just to answer objections, but to live in a visibly different way—a missioholistic way—one that rehumanizes the church’s presence in public life.

Strengths

Smith’s greatest strength lies in his ability to name what many of us have felt but couldn’t articulate. His insights into how forces like the end of the Cold War, neoliberal capitalism, the digital revolution, pop postmodernism, multicultural education, intensive parenting, and mainstream LGBTQ+ advocacy have reshaped public imagination are wonderfully eye-opening. His critiques of New Atheism, institutional distrust, and the third sexual revolution are especially incisive and helpful.

I particularly appreciated his examination of modern evangelicalism. Smith’s critique—touching on religious scandals, mission drift, me-and-God spirituality, biblical foundationalist epistemology, culture war entanglements, power-hoarding leadership, populism, and the lingering effects of the purity movement—further crystallizes his argument, giving further justification of the need to move beyond traditional inherited church forms rooted in modernistic impulses.

For pastors and ministry leaders, this book offers a vital and life-giving vocabulary for understanding what’s happening beneath the surface of their congregations. At Apollos Watered, one of our convictions is that if the gospel isn’t framed clearly and holistically, Western individualism and neoliberal capitalism will distort it beyond recognition. Smith equips us to name those distortions—and offers tools for resisting them.

Section II, Perfect Storms Converging (pp. 73–275), is where Smith’s analysis shines most clearly and forcefully. Few books so thoroughly unpack the way economic systems, social movements, and cultural transformations have progressively “crowded out” Christian faith from the everyday lives of ordinary people. Smith traces how these converging forces didn’t merely erode religious participation—they reshaped the very plausibility structures that once made Christian belief seem natural, necessary, and good.

This is precisely where many pastors and church leaders find themselves today—navigating a world in which a well-meaning family may explain they can’t attend church or serve because of their child’s soccer schedule. It’s easy to chalk this up to distraction or misplaced priorities, but Smith shows that the deeper issue is interpretive: the framework through which people make meaning and form commitments has fundamentally changed.

Ironically, as Smith notes, American Christianity is in many ways a victim of its own success. Its cultural dominance, institutional expansion, and educational influence produced unexpected blind spots—assumptions of stability, moral consensus, and generational continuity that no longer hold. These very strengths have now become sources of fragility. Christianity once shaped the culture, but it now finds itself increasingly shaped by it.

What we are witnessing, then, is not just the loss of influence but the exposure of a shallow theological foundation—what might be called populist theology matured over time in a particular cultural context. It lacked the depth to withstand the perfect storm now battering the church. The implications are profound, and the lesson is clear: we ignore these dynamics at our peril.

Weaknesses

The book is compelling and well-researched, but not without its flaws. Smith’s treatment of religious minorities feels underdeveloped—more an afterthought than a fully integrated theme. And while his diagnosis is strong, the final section offering a way forward is thin in comparison. Those hoping for a hopeful blueprint for renewal may walk away wanting more.

Conclusion

Still, Why Religion Became Obsolete is essential reading for any church leader serving in a Western context, not only in the United States. While Smith focuses primarily on American cultural dynamics, the patterns he identifies resonate far beyond U.S. borders. Many of his insights can be transposed to any setting shaped by Western influence, where the erosion of religious plausibility is unfolding in similar ways. The book gives language to the silent questions many are already asking and brings clarity to the complex challenges now confronting pastors, missionaries, and everyday Christians alike.

It offers far more than another critique of declining church attendance or cultural shift. It’s a clarifying voice for those seeking to renew the Church for the mission of God. We cannot move forward until we understand what went wrong—and why people are no longer asking the same questions we’re trying to answer.

If you’re tired of “try harder” solutions and ready to engage the real cultural challenges before us, this book will give you clarity, language, and insight. Then, together, we can begin the hard work of building something faithful, beautiful, and resilient for the world to come.

The Apollos Watered Rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐—Must Read—this book is essential for your library.

The Apollos Watered Review Rating System:

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Must Read: Foundational, insightful, and transformative for ministry leaders. Everyone in your sphere should read it.

⭐⭐⭐⭐½ Nearly Essential: Excellent and compelling. Just shy of “must read,” but still highly recommended.

⭐⭐⭐⭐ Should Read: Strong contribution. Valuable for most readers in your context.

⭐⭐⭐½ Helpful if Interested: Worthwhile for those with a specific interest or need.

⭐⭐⭐ Situationally Useful: Some good insights, but not broadly applicable. It might serve a limited purpose.

⭐⭐½ or less Skim or Leave It Be: Little lasting value. May have a point or two, but better options are available.

⭐½ or ⭐Skip It: Weak or misleading. Not worth your time.